What's Happening in OER in Africa

What's Happening in OER in Africa

This section provides latest updates to news and events relating to OER in African higher education and will include notices to new policies, research, events/conferences.

Displaying 1 - 107 of 107Academic librarians can be at the forefront of helping users wade through the hyperbole, challenges, and benefits of AI. They have always been considered ‘the gatekeepers’ of knowledge. They can also open the door to better understanding of new technologies and concepts.

Image courtesy of Hal Gatewood, Unsplash

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has assumed a leadership role in discussions about education. Neil Butcher’s blog on AI’s false promises in education lays out major issues and pinpoints the easy assumptions on AI’s importance to educational systems.[1]

Academic librarians can be at the forefront of helping users wade through the hyperbole, challenges, and benefits of AI. They have always been considered ‘the gatekeepers’ of knowledge. They can also open the door to better understanding of new technologies and concepts.

African libraries have been trailblazers in adopting technology. In the 1990s, librarians in countries like Malawi, Ghana, and Nigeria were responsible for email in their institutions and countries. In those days, there was no viable Internet, and email was based on store and forward messaging. Emails would be stored on a computer system and then forwarded to the organization responsible for distributing them.[2]

Christine Kisiedu, then university librarian of the University of Ghana wrote:[3]

"It is often said that once ICT [Information and Communications Technology] development gets underway, it is unstoppable. This was certainly the case in Ghana. When a workshop on Electronic Networking for West African Universities (sponsored by the Association of African Universities and the American Association for the Advancement of Science) took place in Accra in December 1993, Ghana was not counted among the Internet savvy countries of the sub-region. Two years later, in 1995, a nationwide store-and-forward e-mail system had been established, and the first professional ISP in Ghana appeared on the scene and introduced Internet access to an interested but cautious Ghanaian public. In another year, development and patronage had reached such a level that Ghana could be said to be on the verge of an Internet explosion! Yet coming to grips with the new technology was not without its ups and downs.

…Learning to use the system proved more difficult than anticipated. I had just completed my second year as University Librarian at the Balme Library when we acquired e-mail…Nobody on the library staff had a clue as to how to operate this technology, much less how it worked. I submitted myself to a brief half hour’s explanatory session, which I must now publicly admit went in one ear and out the other. The consultant took too much for granted!"

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is the latest and trending ICT development, and again academic libraries are playing a leadership role.[4] The librarian of Northwestern University in the United States curates a page on the library platform on Using AI Tools in Your Research.[5] Other universities have done the same. A Google search for ‘library guides AI’ pulled up scores of university libraries offering AI guidance:

In a recent blog post on AI and educational technology, referred to above, Neil Butcher pointed to the disparities between what we know about AI and its impact on education. He emphasized that international groups like UNESCO are promoting AI’s success with little evidence to go on. Butcher wrote:[6]

"ChatGPT was only launched in November, 2022 but, by 2021, UNESCO had already launched a full publication entitled AI and Education that provides guidance to policy-makers. It seems a remarkable achievement that the world’s largest educational intergovernmental organization already felt confident enough in its understanding of the educational use of technologies about which we know so little and whose potential wider social impact is so little understood to offer unequivocal policy guidance on their use to governments. Having worked in educational policy for many years, my instinct is that it will be several years before we know enough about these issues to be clear about the policy implications."

The African Library and Information Associations and Institutions (AfLIA) and OER Africa decided to ask African academic librarians about their experiences and thoughts on AI. Nkem Osuigwe, AfLIA Director of Human Capacity Development and Training, put out a call on the AfLIA-OER Africa WhatsApp group. She wrote:[7]

"Have you ever noticed how technology seems to throw up opinions about the relevance of libraries?. Remember when the Internet went mainstream, and there were all sorts of permutations about the survival of libraries? Many asked if the Internet would replace libraries. When artificial intelligence became the new buzz concept, quite a number of librarians jumped in to talk about robots and what they can be used for in libraries.

Now, generative AI is the new rave. Young and old can do research on AI platforms, and within seconds, 'everything' is delivered, including references. Generative AI is creating art, writing essays, poems, short stories, drama, newspaper articles, and even social media posts.

Who needs libraries now, one may ask!. The verdict is not in yet. However, in Africa, we want to begin to tell our stories by ourselves about how libraries could use this technology so that we can 'own' the narrative about the tool.

• what impediments do we foresee in the advancement of AI?

• Can information literacy modules/classes and/or Use of Library courses introduce our users to 'ethical' AI?

• Can librarians assist in detecting when people are attributed for work by generative AI?

• Copyright and licensing issues are bound to crop up with the continued use of AI. Can African librarians help on creating awareness about this?

Generally, we’d love to hear about our interactions with AI as African librarian."

Librarian responses have been numerous and interesting. They are still coming in. Below are some examples of experiences reported:

The University of Ghana has revised its plagiarism policy to include use of AI:[8]

"Any employment of AI or associated technologies that compromises the authenticity of academic output will be deemed unacceptable,’ the document stated.

The University stresses originality in scholarly work, addressing AI's role in academic integrity.

The policy update underscores a commitment to ethical academic practices, leveraging technology while upholding original thought."

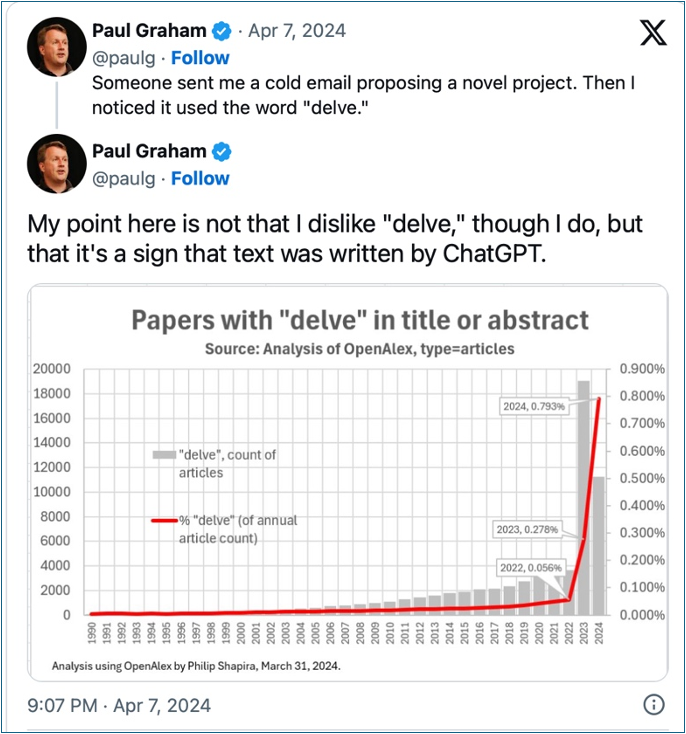

Researchers from the global South are accused of using AI if the language of their research papers and proposals use uncommon words like ‘delve’. One participant commented on vocabulary and AI:

"There was an uproar last week on Twitter. An American funder got a good project proposal, but ditched it because he saw the word 'delve' and thought the proposal was AI generated, because he doesn't write using these fancy words; only machines do.

Apparently, some words are already been termed AI generated words, and so AI detectors would look for such words and flag.

What happens when we use these words frequently in our write ups?"

The tweeter was Paul Graham, co-founder of Y-Combinator and this is what he wrote:[9]

Graham’s post has been widely controversial, with many researchers responding that they use these types of vocabularies. For many people for whom English is a second language or who normally use an extensive vocabulary, words like ‘delve’ are a part of their writing and not AI generated.

Another participant noted:

"Africans, mostly Nigerians, jumped on the Twitter (now X) thread to point out that we write that way. I actually do. It appears that AI is yet to learn the difference between English spoken or written as a first language and how those who got it as a second language communicate with it.

It is functional prejudice that has been taken on by AI. What do I mean? If you play word games online, especially those created by those who have English as their 1st language, you would be amazed at the words that pop up as correct options. This supposition is still being tested, though, but Africans use more of 'official' and 'bogus' words more than the owners of the language. AI may have picked up that trait from the owners of the language."

In general librarians agreed that neither Internet nor AI can replace the library and used Nile University in Egypt as an example:

"If the Internet could not replace libraries, I don't see how AI could take the place of a library. Remember, we provide many services, and for now, I have seen scholars use AI Mostly for research purposes. Any good researcher should know that in conducting research, you cannot depend on AI tools alone; you have to consult other information resources. Just like what Nile University library is undergoing, librarians should see the coming of AI to our advantage and introduce newer services such as information literacy, how to detect plagiarism, and ethical issues among others."

More broadly and beyond AI, libraries play an essential role for all members of the academic community:

"Libraries need to consider transforming their spaces in research and learning Commons. The trend is catching on fast as some libraries also have worker and creator spaces. The client should feel as though they are in a one-stop shop where they can learn something and transform it into a prototype or sample product. Not only can we help job seekers, but we can hold meetings with guest authors. We can, if funds permit, partner a publisher to bring an author’s work to life in the library. My personal concern is the lack of partnerships and the slow evolution in our library spaces and the lack of recognition for those who spark creativity. I miss the time many people would speak about a book or library inspiring them. The voices are few, and a new crop that rejects the education system (inclusive of the library) is getting popular. Save for the places with a strong reading culture and push for education."

The WhatsApp AI discussions were informative and spanned the breadth of existing and possible interactions with their constituencies. AfLIA has made recommendations for libraries that want to engage more fully with their university communities on this topic:

Lack of knowledge about technology creates unfounded trepidation. AfLIA encourages African librarians to view AI as a tool for discovering more knowledge and reference sources for their user communities. Generative AI is a Large Language Model that is trained using large mostly open datasets. Viewing it through this prism will give librarians the understanding that generative AI recycles and collates already existing knowledge. That is an area in which librarians excel! African librarians have another advantage—the datasets AI uses do not include sufficient African source material, AI source materials therefore underrepresent African knowledge. Academic librarians understand the importance of appropriately indexing content, which is essential when considering datasets. African academic libraries and other institutions, such as archives, contain source material coming from Africa—both original sources and research content about African knowledge.

Innovation in information access is unstoppable. It is imperative that academic librarians adopt an open and adaptive attitude toward new developments. AI, including generative AI, just as any other tool or resource, has its limitations. But being apprehensive and unreceptive towards AI, probably with the intention of gatekeeping ‘a profession under threat’, is not sustainable – a lesson history has taught us time and again. In fact, that mindset numbs the innovative capacity of librarians and institutions to adapt and provide valued services to fill the gaps developed because of the limitations of generative AI. We must embrace it as an opportunity to evolve and better serve our patrons.

The time has come for African academic librarians to deepen engagement and collaboration across universities, both locally and internationally. The challenges faced by the profession can no longer be considered local, hence operating in silos is not viable. Through collaboration, we can collectively debate, brainstorm, exchange best practices, and share insights on what actions or decisions are being taken by academic institutions to address pressing issues like academic ethics, plagiarism, originality of thought, copyright, misinformation, disinformation etc. that have resurfaced, following the birth of AI resources like ChatGPT and Gemini.

The application of information ethics principles is important while engaging with generative AI. African librarians can lead the way in teaching and inculcating ethical skills in the use of generative AI through information literacy skills or use of library tutorials. The Wikipedia article on ethics and AI outlines key points of intersection:[10]

"The ethics of artificial intelligence covers a broad range of topics within the field that are considered to have particular ethical stakes. This includes algorithmic biases, fairness, automated decision-making, accountability, privacy, and regulation ."

AfLIA strongly encourages African librarians to understand and promote Openness as an avenue for making datasets available for training generative AI. In an article on AI and data, published by European Data, the authors make a number of points about the relationship between AI and data, including:[11]

"Open data and AI have the potential to support and enhance each other’s capabilities. On the one hand, open data can improve AI systems. In general, exposing AI systems to a larger volume and variety of data increases the chance of the system returning accurate and useful predictions. As such, open data can be a supply of large amounts of diverse information for AI systems. In this way, the availability of open data contributes to better performing AI."

If African librarians are to play a role in discussions about data, openness, and AI, they must understand the importance of data. The AfLIA collaboration with Wikimedia on data short courses[12] is important. But this work must delve more deeply into the significance of these relationships.

Library and information institutions may not directly dictate the data utilized in training various generative AI models to ensure a balanced perspective on African knowledge. However, it is vital for stakeholders to intensify advocacy so that African researchers, educators, librarians, and authors in general can embrace openness. Making African knowledge more accessible through open research, open data, and open educational resources can improve the availability of diverse and representative data used to train AI models.

Related articles:

- Artificial Intelligence and the Underrepresentation of African Languages

- Three Ways Artificial Intelligence Could Change How We Use Open Educational Resources

- Opening Education: What Role Do Librarians on the African Continent Play?

[1] Neil Butcher, False Promises about ‘AI’ in Education. 19 April 2024. https://www.nba.co.za/encounters/blog/false-promises-about-ai-education

[2] See Wikipedia on store and forward messaging. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Store_and_forward - :~:text=Store and forward is a,or to another intermediate station.

[3] [3] Christine Kisiedu’s story featured in Rowing Upstream: Stories of the Information Age in Ghana published with Ford Foundation funding in 2002. It is available on the Wayback machine. Go to https://web.archive.org/web/20031220201222/http://www.piac.org/rowing_upstream/chapter7/ch7bringing.html for Christine’s recounting of email introduction into the University of Ghana.

[4] Go to AI, the Next Chapter for College Librarians by Lauren Coffee in Inside Higher Ed, November 3, 2023, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/tech-innovation/libraries/2023/11/03/ai-marks-next-chapter-college-librarians

[6] False promises about ‘AI’ in education, Neil Butcher, April 19, 2024, https://www.nba.co.za/encounters/blog/false-promises-about-ai-education

[7] Nkem Osuigwe, AfLIA-OER Africa Training WhatsApp group

[8] University of Ghana revises its plagiarism policy to clamp down on AI usage in academic work. Jemima Okang Addae. February 26, 2024. Graphic Online. https://www.graphic.com.gh/news/general-news/university-of-ghana-revises-its-plagiarism-policy.html - :~:text=The updated policy notably includes,unacceptable,’ the document stated

[9] Ana Altchek, Y Combinator cofounder Paul Graham says seeing this word in an email pitch is a sign it was written by ChatGPT, Business Insider. April 10, 2024. https://www.businessinsider.com/y-combinator-paul-graham-delve-ai-chatgpt-giveaway-email-pitch-2024-4

[10] Ethics of Artificial Intelligence, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ethics_of_artificial_intelligence - :~:text=The ethics of artificial intelligence covers a broad range of,accountability, privacy, and regulation.

[11] Open data and AI: A symbiotic relationship for progress. European Data. June 9, 2023. https://data.europa.eu/en/publications/datastories/open-data-and-ai-symbiotic-relationship-progress

[12] Wikidata short course, https://web.aflia.net/aflia-wikidata-online-course-registration-now-open/

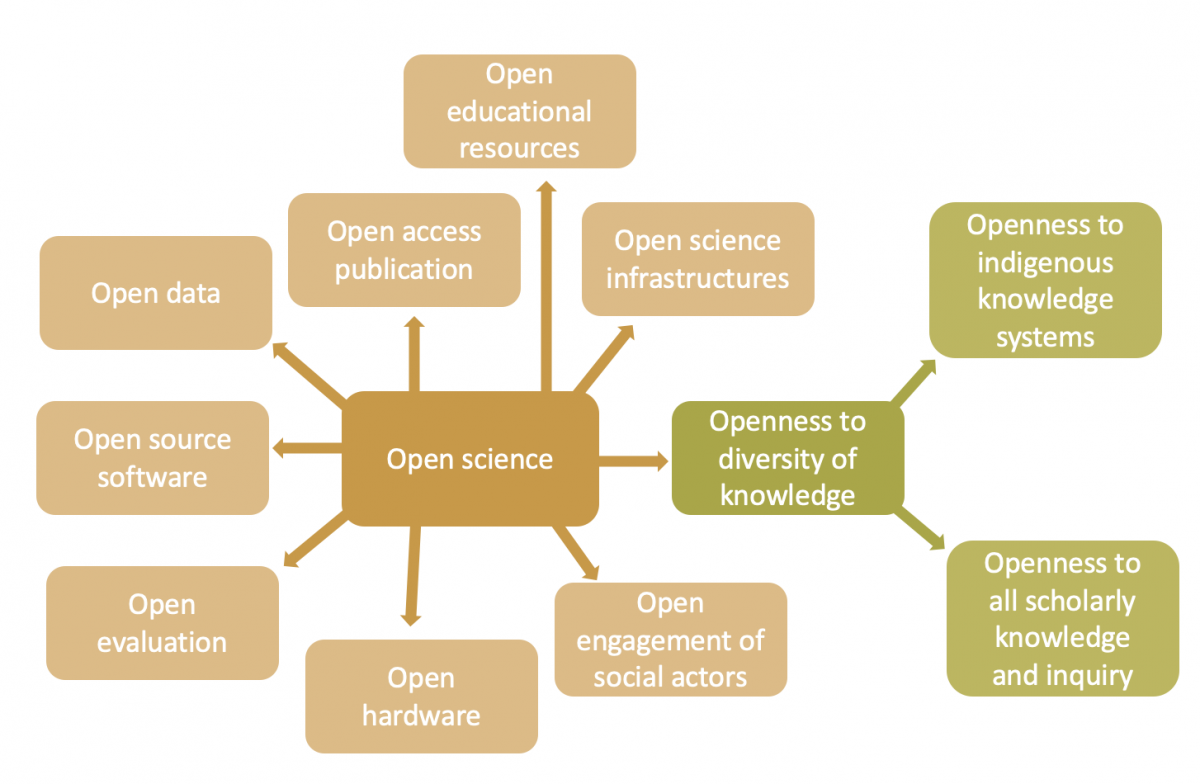

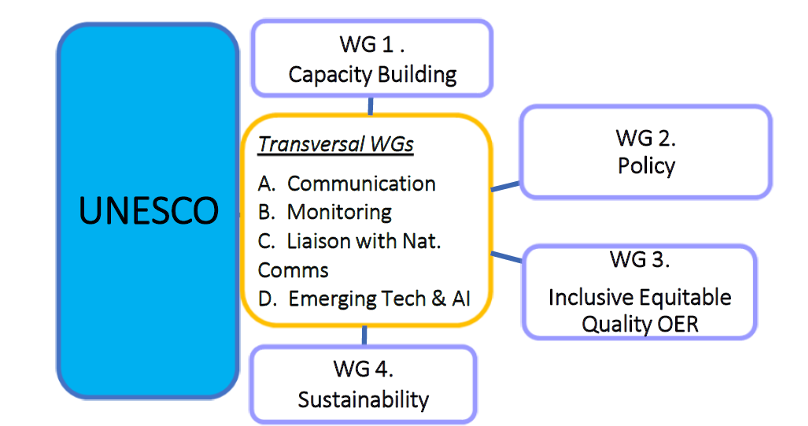

Following the adoption of the OER Recommendation in 2019, UNESCO initiated a programme to support governments and educational institutions in implementing it.

One aspect of this programme was the development of a series of five guidelines to inform implementation of each Action Area in the Recommendation.

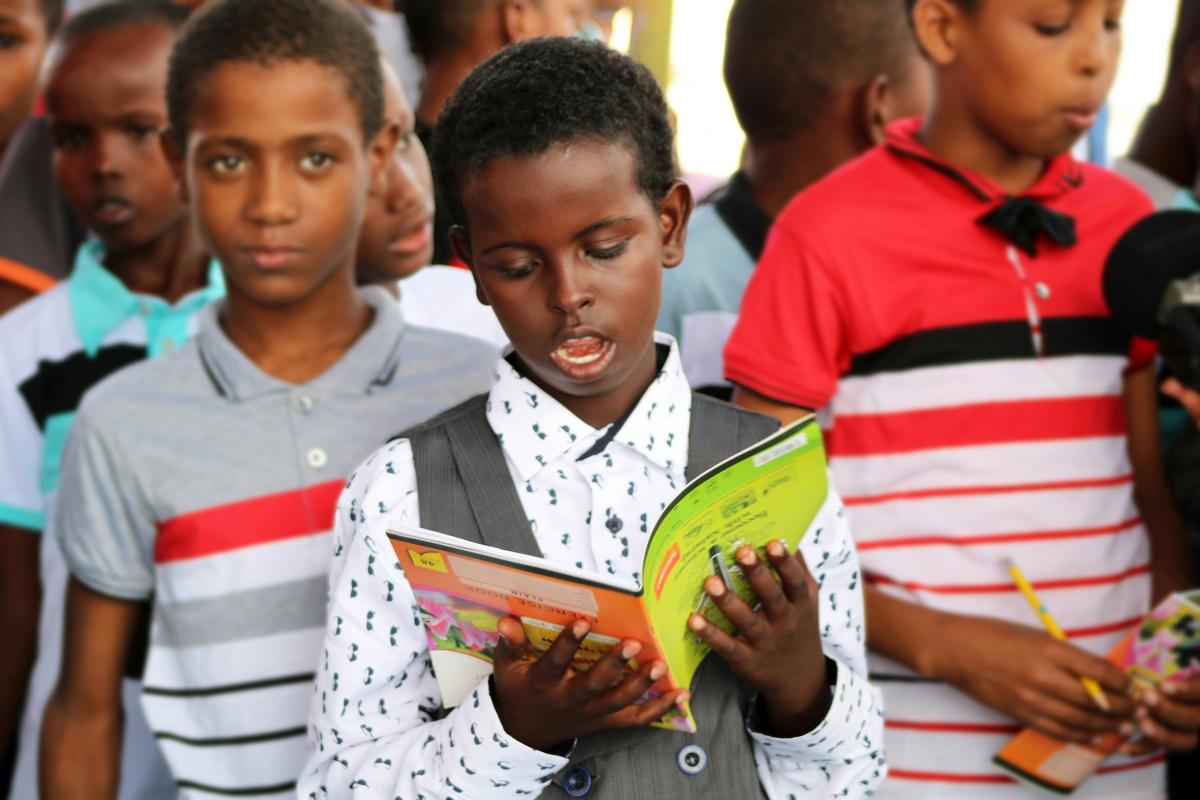

Image courtesy of Ismail Salad Osman Hajji dirir, Unsplash

As the digital age continues to reshape the global educational landscape in fundamental ways, the need for governments and educational institutions to champion Open Educational Resources (OER) has never been more relevant. Freely accessible, openly licensed educational content can help tackle some of the most pressing needs in education systems, including equity, access, and quality.

Following the adoption of the UNESCO Recommendation on OER at the 40th UNESCO General Conference in Paris on 25th November 2019, UNESCO initiated a programme to support governments and educational institutions in implementing the Recommendation.

One such action was the development of a series of five guidelines for governments. These guidelines were developed through a comprehensive consultative process and in cooperation with OER experts worldwide. They draw heavily on in-depth background papers prepared by OER experts from around the world in each of the five Action Areas of the OER Recommendation: Prof. Melinda dP. Bandalaria (building the capacity of stakeholders to create, access, re-use, adapt and redistribute OER); Dr Javiera Atenas (developing supportive policy); Dr Ahmed Tlili (encouraging inclusive and equitable quality OER); Dr Tel Amiel (nurturing the creation of sustainability models for OER), and Ms Lisbeth Levey (facilitating international cooperation).

OER Africa has provided logistical and editorial assistance to UNESCO on this work as part of a formal cooperation agreement with UNESCO to provide support in implementation of the OER Recommendation.

Aimed at governments and educational institutions, each set of guidelines has the following structure:

- An overview of recommendations in the Action Area;

- An introduction to the main issues surrounding the Action Area;

- A matrix of possible actions recommended for governments and institutions to implement each point in the Action Area;

- An in-depth discussion of the key issues surrounding the Action Area; and

- Examples of good practice.

By actively supporting and implementing the OER Recommendation, governments and educational institutions can not only make high quality education more accessible but can also promote transformation in their education systems. This commitment to OER is essential for building resilient, adaptable education systems that can meet the demands of a rapidly changing world.

Related articles

With the ever-increasing costs of textbooks, how can university students get access to the resources they need to study? This article examines the benefits of using open textbooks in the Global South.

Image: CC0 (Public domain)

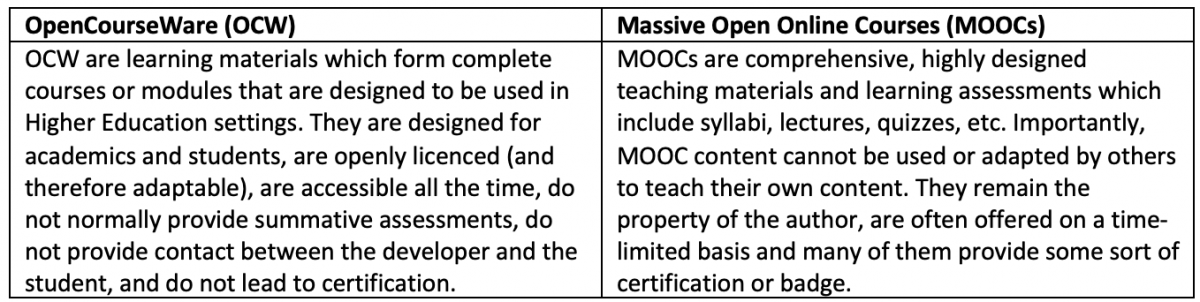

With the ever-increasing costs of textbooks, how can university students get access to the resources they need to study?

Worldwide, university students find it difficult to purchase textbooks for their courses as they are too expensive. Already in 2014 in South Africa[1], and in 2011 in the United States[2], there were reports that students didn’t buy textbooks due to expense. The situation has not improved in recent years; for example, in a study of nearly fifty thousand respondents in South African universities, nearly two thirds indicated that they spent between R500 and R2500 on textbooks, and while 87% of students’ first semester modules had prescribed textbooks, 27% of students did not buy any prescribed books in the first semester of 2020. Students were opting not to purchase textbooks either because of a lack of affordability, because they did not find them contextually relevant, or because a course would only use a small portion of the textbook. [3]

Open textbooks can be regarded as a subset of Open Educational Resources (OER). They are digital textbooks published under an open licence, which means that they are freely downloadable and adaptable to suit a range of contexts (as long as the licence permits adaptation). The right to adapt is particularly important for educators who may want to tailor the textbook to their specific curriculum. An open textbook can be published with different Creative Commons licences,[4] depending on how open or restrictive the author wishes the licence to be. The principal advantages of an open textbook are its accessibility and affordability to the students, as long as they have a digital device, or have access to print at low or no cost. However, open textbooks have other advantages as well. These include:[5]

- Local Contexts: Open textbooks can be regularly updated, and tailored to suit the local context, providing cultural relevance and addressing specific needs of students.

- Partial Use: In some courses, only a portion of the overall textbook content is relevant. Students may hesitate to purchase an expensive textbook when they will only use a few chapters. In contrast, open textbooks allow educators to select and integrate specific sections, reducing unnecessary costs.

- Collective Authorship: Open textbooks encourage collaborative authorship strategies. Locally produced open textbooks can involve input from multiple experts, resulting in richer and more contextually relevant content with diverse perspectives.

- Flexibility: Open textbooks can be accessed in different formats and stored digitally, so that they are easy to share and adapt.

Of course, open textbooks also have some disadvantages, namely:

- Availability: We provide examples of open textbook repositories below, but educators may find that there is limited selection for certain subjects or specialised topics.

- Quality: There may be inconsistencies in writing style, accuracy, and depth of content but these can be easily mitigated by evaluating the textbooks prior to use, as should be done for all resources to be used, including commercial textbooks.

- Author incentives: Authors of traditional textbooks normally receive royalties from publishers as their books are sold. The open licence by which open textbooks are released means that other forms of incentive may be needed, for example in the form of grants, that may not be sufficiently enticing for many potential authors.

Research on open textbooks

Most research has been carried out in the Global North. For example, a meta-analysis of 22 studies of 100,012 students found that there were no differences between open and commercial textbooks for learning performance.[6] A research study Adoption and impact of OER in the Global South[7] had similar findings, with open textbooks being more effective that traditional ones in several instances. However, the studies reported that careful pedagogical scaffolding, including a mix of OER, produced the most effective learning. Within Africa, research findings from the Digital Open Textbooks for Development (DOT4D) Project[8] found that open textbooks addressed economic, cultural, and political injustices faced by their students, issues not considered by traditional textbooks. Summarising the research overall, we can say that open textbooks have several advantages over traditional ones, as listed above, and in terms of learning, they are equivalent.

Examples of African institutions who have benefited from using open textbooks

Probably the best example of collaborative development of open textbooks is the University of Cape Town’s DOT4D Project. If you want to learn about the experiences of their staff and students, read UCT Open Textbook Journeyswhich documents the stories of 11 academics at the University who embarked on open textbook development initiatives to provide their students more accessible and locally relevant learning materials.

Other African universities’ libraries list sites where open textbooks and other OER are available, usually from outside the continent. Finding open textbooks for your own institution is not always easy. Here we list three sites where you can search for open textbooks. Bear in mind that, if you choose an American or European textbook, you may need to spend time adapting it for your own context.

University of Cape Town Catalogue

26 textbook titles ranging from medical texts, through sustainable development to marketing, but also many other titles on OpenUCT.

Based at the University of Minnesota in the United States, this repository has 1,403 titles. The view shown here groups the titles by subject.

This LibGuide lists 17 platforms where you can search for open access textbooks and other free books.

Resources on developing and using open textbooks

Below is a list of resources to help you explore this growing field. The first three assist you to develop an open textbook, while the last two guide you to adopt or modify an existing open textbook.

- Commonwealth of Learning Guide to Developing Open Textbooks

- Open Education Network: Authoring Open Textbooks

- Rebus Community: A guide to making open textbooks with students

- BC Campus: Steps to Adopting an Open Textbook

- Open Education Network: Modifying an Open Textbook: What You Need to Know

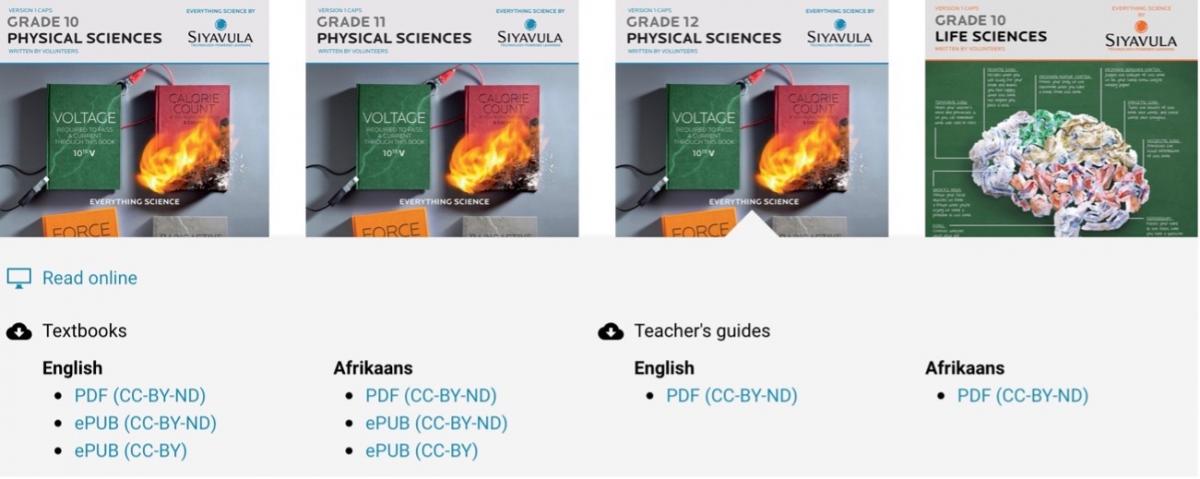

Finally, although they are not designed for higher education, the open textbooks developed by Siyavula for high school mathematics, technology, and sciences may be useful for colleges and access courses in universities.

In summary, there are considerable benefits to using open textbooks, but with a few exceptions, African institutions have not yet taken on the challenge of producing open textbooks themselves. Clearly, funding is required for the development of open textbooks, and institutions might consider making funding applications to create (or adapt) these highly useful open education resources for the benefit of more African students.

Related resources:

- Researching OER initiatives in African higher education

- The Revised Open Knowledge Primer for African Universities

- Self-Publishing Guide: BC Open Textbook

Access the OER Africa communications archive here

[1] Nkosi, B. (2014). Students hurt by pricey textbooks. Mail & Guardian. Retrieved from https://mg.co.za/article/2014-10-03-students-hurt-by-pricey-textbooks/

[2] Redden, M. (2011). 7 in 10 Students Have Skipped Buying a Textbook Because of Its Cost, Survey Finds. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from https://www.chronicle.com/article/7-in-10-students-have-skipped-buying-a-textbook-because-of-its-cost-survey-finds/

[3] Department of Higher Education. (2020). Students’ Access to and use of Learning Materials—Survey Report 2020. Retrieved from https://www.usaf.ac.za/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/DHET_SAULM-Report-2020.pdf

[4] See https://creativecommons.org/share-your-work/cclicenses/#:~:text=Creative%20Commons%20licenses%20give%20everyone,creative%20work%20under%20copyright%20law.

[5] Digital Open Textbooks for Development. (2021). ‘Open Textbooks in South African Higher Education’ Roundtable Report. University of Cape Town. Retrieved from https://open.uct.ac.za/server/api/core/bitstreams/3a7e1a09-0617-4ba4-b6dd-4572bd870d60/content

[6] Clinton, V. and Khan, S. (July 2019). ‘Efficacy of Open Textbook Adoption on Learning Performance and Course Withdrawal Rates: A Meta-Analysis’ AERA Open. 5 (3): 233285841987221. doi:10.1177/2332858419872212. ISSN 2332-8584.

[7] Hodgkinson-Williams, C. & Arinto, P. B. (2017). ‘Adoption and impact of OER in the Global South’. Cape Town & Ottawa: African Minds, International Development Research Centre & Research on Open Educational Resources. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.1005330

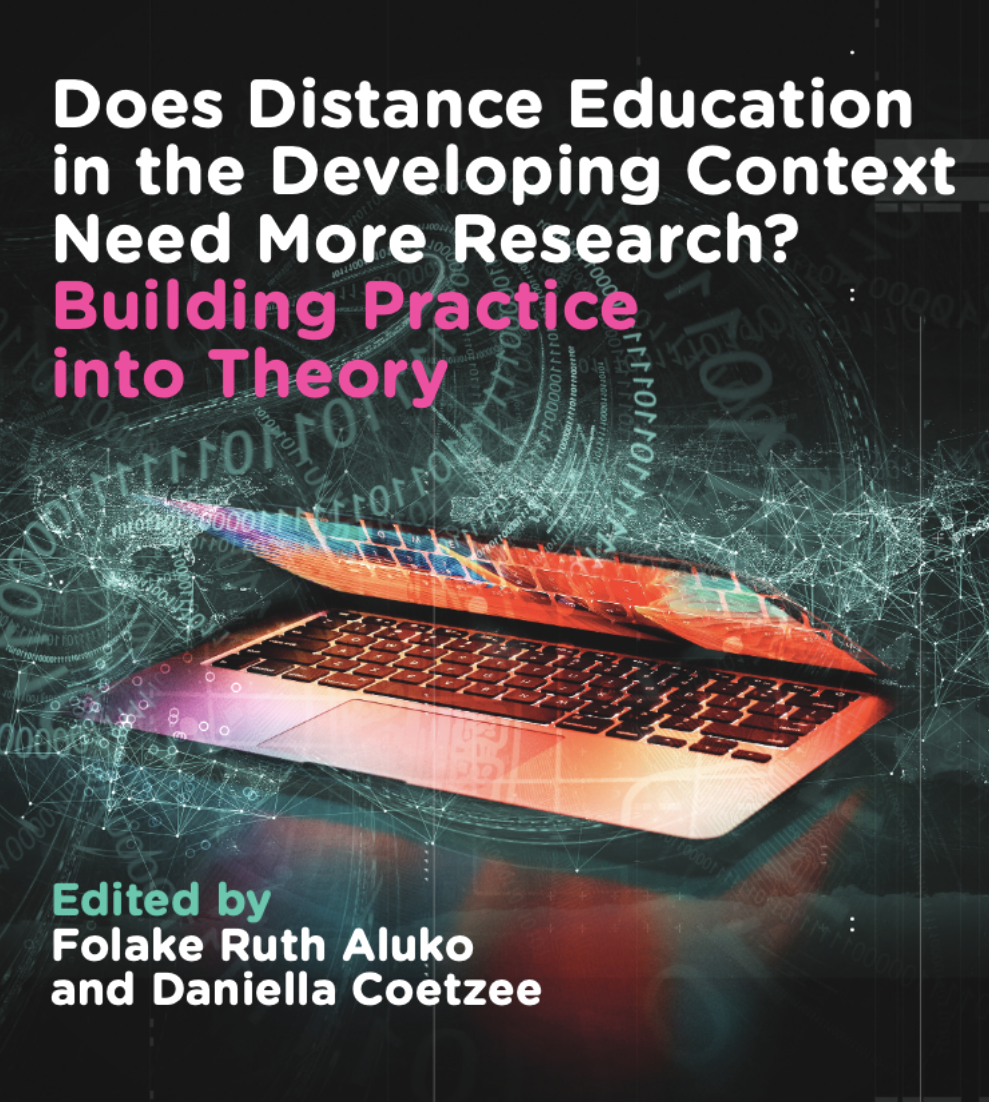

OER Africa is honoured to have contributed two chapters to the recently published book ‘Does Distance Education in the Developing Context Need More Research? Building Practice into Theory’. Edited by Dr Folake Ruth Aluko and Prof. Daniella Coetzee, the book explores the reciprocal relationship between theory and practice in distance education.

Research can have a transformative impact on any field, and distance education is no exception. It can, for example, contribute to more effective use of new educational strategies, provide insights into technological advancements, and contribute to our understanding of the key successes and challenges in distance education delivery.

While the concept of distance education dates back more than a century, research in this area is relatively nascent when compared to the development of educational research in general.[1] The body of literature on the practice, influence, and impact of distance education is therefore limited, and even more so when considering developing world contexts. This, combined with the fact that distance education is experiencing significant shifts in terms of new demands and evolving technologies that provide new potential and pitfalls alike, mean that the recently published book Does Distance Education in the Developing Context Need More Research? Building Practice into Theory is a critical addition to the distance education research literature.

The book explores the reciprocal relationship between theory and practice in distance education, and OER Africa is honoured to have contributed two chapters to it. Edited by Dr Folake Ruth Aluko and Prof. Daniella Coetzee, the book is divided into two volumes which explore various themes:

Volume 1 focusses on the history, approaches and paradigms in distance education; building frameworks in distance education research; and praxis in this area.

Volume 2 moves on to address regional trends and gaps in distance education research; scholarship in this area; and quality assurance.

The two chapters that we contributed focus on the intersection of distance education and catalysing open education praxis, with each chapter approaching this intersection from a different angle. Each is outlined below.

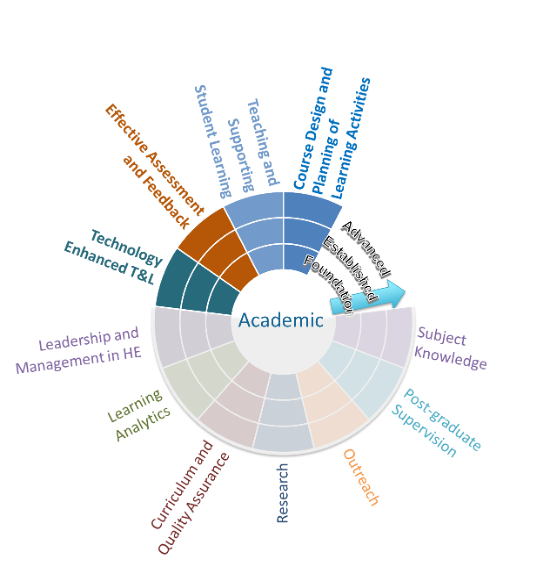

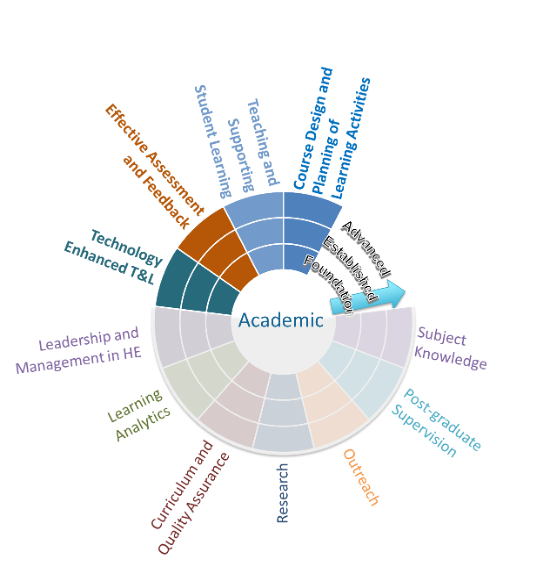

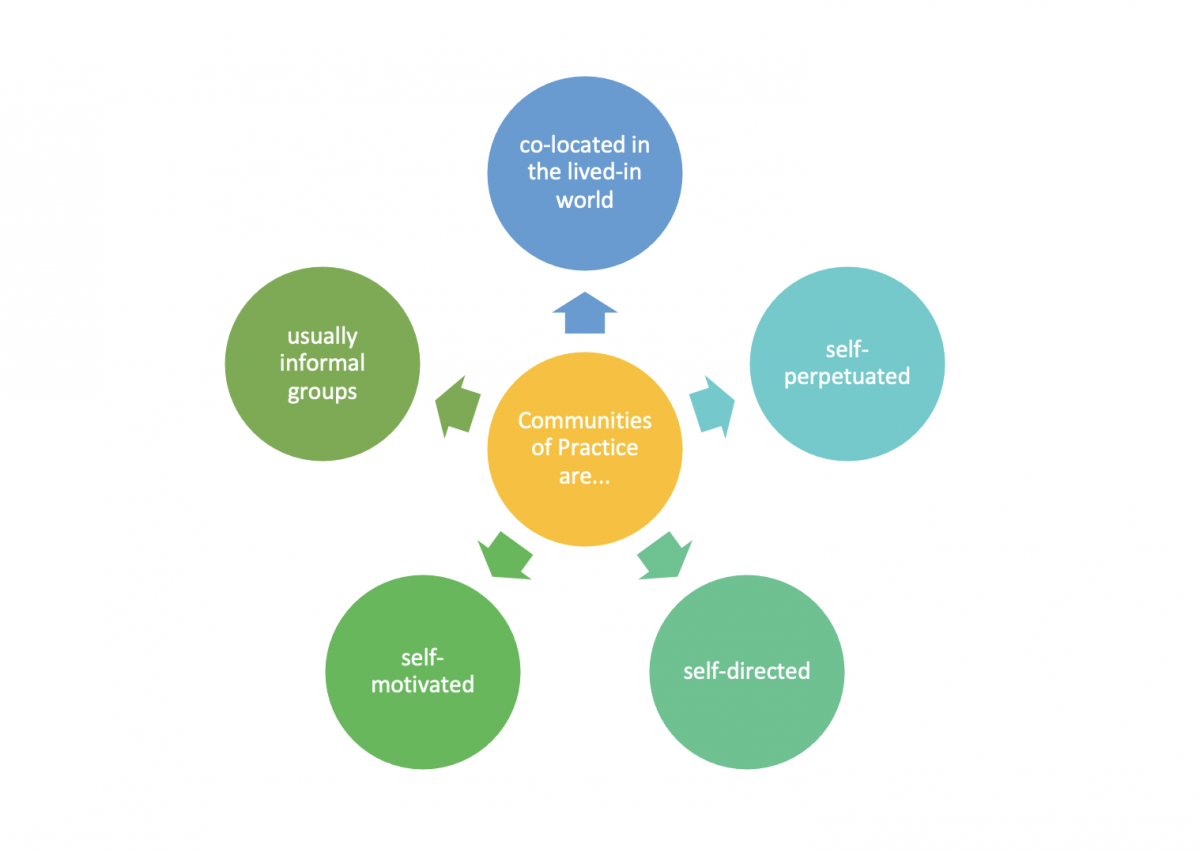

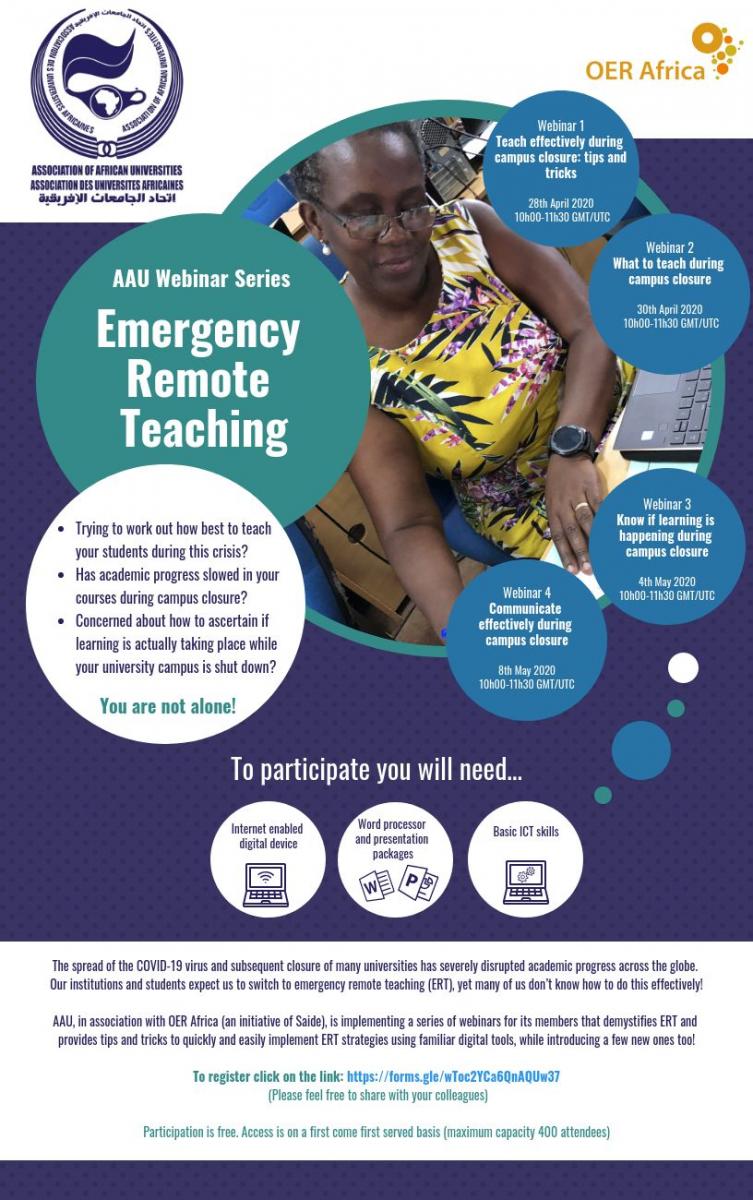

The COVID-19 pandemic brought the importance of professional development on effective teaching and learning for university academics into sharp relief. Universities found themselves having to close their campuses and were unable to teach their students face-to-face. Universities in Africa resorted to various strategies to reach students, ranging from no teaching taking place, through emergency remote teaching (ERT) with some form of online teaching, to fully implemented e-learning. Whatever form the teaching has taken, academics have found that traditional lecturing has not been effective when implementing ERT or online teaching. Those who are experienced in adult pedagogies have been expressing the inadequacies of the lecture mode for many years, and the realities of the new forms of teaching required have brought such shortcomings to the fore. Several recent opinion pieces have expressed the need for continuing professional development (CPD) of academic staff, especially with respect to their teaching competence, arguing that it needs to be a central strategy within higher educational institutions (HEIs) around the world, supporting academics with digital teaching and communities of practice.

This chapter opens with a review of successful and innovative CPD models and approaches used in HEIs around the world. It examines recent CPD activities created by OER Africa and describes their development, piloting, and deployment, together with the implications the pilot findings have for ODL institutions and research in the field.

Chapter 13 - Measuring implementation of UNESCO’s OER Recommendation: A possible framework

Drawing on a comprehensive literature review of best practice in OER measurement, as well as experience of working with UNESCO to support implementation of the Recommendation, this chapter presents an initial framework for the measurement of the effectiveness of the OER Recommendation and proposes indicators that regions, countries, and/or institutions could adopt or adapt to rigorously measure both how OER is used and its effectiveness for improving learning. Putting in place shared understandings of what counts as effectiveness for OER is critical to inform ongoing developments and improvements in the field. Such measures can also provide an evidence base that can be used for advocacy work around the importance of OER for quality open and distance learning.

Access both volumes below:

Related articles

- How can we plan professional development in universities?

- The UNESCO OER Recommendation and effective, inclusive, equitable access to quality OER

- Continuing Professional Development strategies in Higher Education Institutions Report

[1] Zawacki-Richter and Naidu (2016) quoted in Aluko, F.R. and Coetzee, D. (2023). Chapter 1: Setting the scene – Why research distance education? In Does Distance Education in the Developing Context Need More Research? Building Practice into Theory. ESI Press:

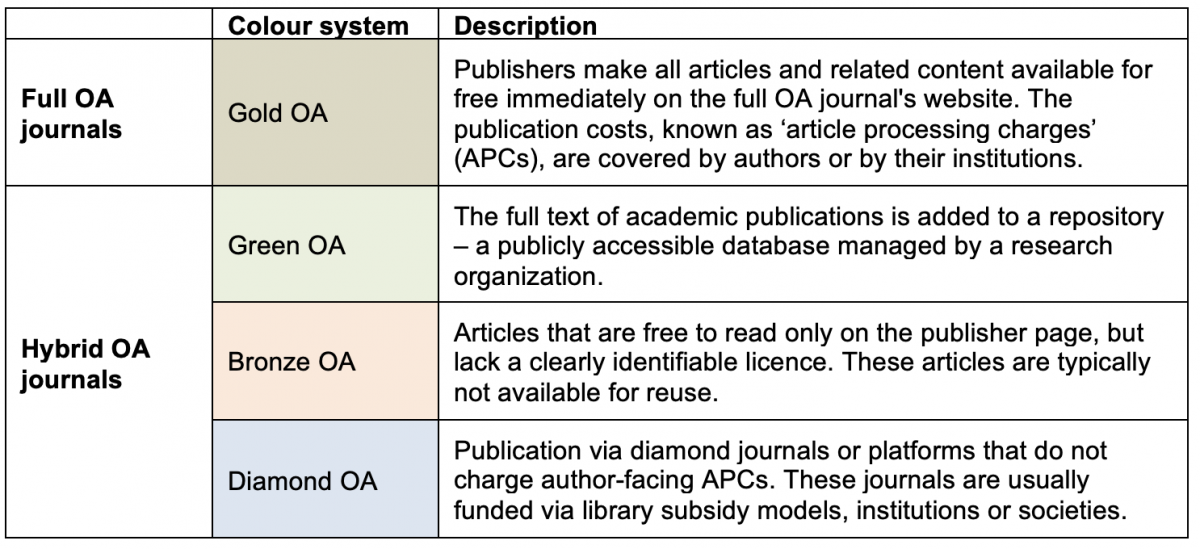

Why might you want to publish your research in an open access journal? Open access journals use Creative Commons licences, which lay out the terms under which they can be used and distributed. Although most open access journals are highly respected and entirely legitimate, there are scores of journals that can be classified as ‘predatory’; they prey on the unwary who want to publish or to read a reliable article.

Introduction: Why is open access publishing beneficial to academics?

Why might you want to publish your research in an open access journal? Open access journals use Creative Commons licences, which lay out the terms under which they can be used and distributed. All Creative Commons licences require full attribution. Open access can benefit scholars because wider access to their research, enhances visibility and citations.[1]

Figure 1 shows some of the possible benefits of OA publishing, many of which are relevant to researchers around the world, including those in Africa.

Figure 1: Benefits of open access publishing

What are predatory journals?

Most open access journals are highly respected and entirely legitimate. The Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ) lists more than 20,000 journals, many without an author processing fee:

Figure 2: DOAJ coverage[2]

The Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET) in South Africa includes the DOAJ journals amongst its list of accredited journals. Academics, researchers, and librarians are sure to find a reliable open access journal on the DOAJ database or any of the others that DHET lists.[3]

Even so, there are scores of journals that can be classified as ‘predatory’; they prey on the unwary who want to publish or to read a reliable article.

What is a predatory journal? In 2019, a group of legal experts and publishers agreed on this definition:

"Predatory journals and publishers are entities that prioritize self-interest at the expense of scholarship and are characterized by false or misleading information, deviation from best editorial and publication practices, a lack of transparency, and/or the use of aggressive and indiscriminate solicitation practices."

Though it might seem straightforward, there are so many forms of predatory practices that this group of specialists had trouble agreeing on a definition to describe how predation manifests itself.[4]

Experts [5] believe that there are now more than 15,000 predatory journals, which promise:

- Peer review with a fast turnaround time.

- Low author processing fees—low in comparison to some of the top tier journals, but high in terms of what authors get for their money.

- Online publication and visibility.

- Indexing in platforms such as Scopus and Web of Science.

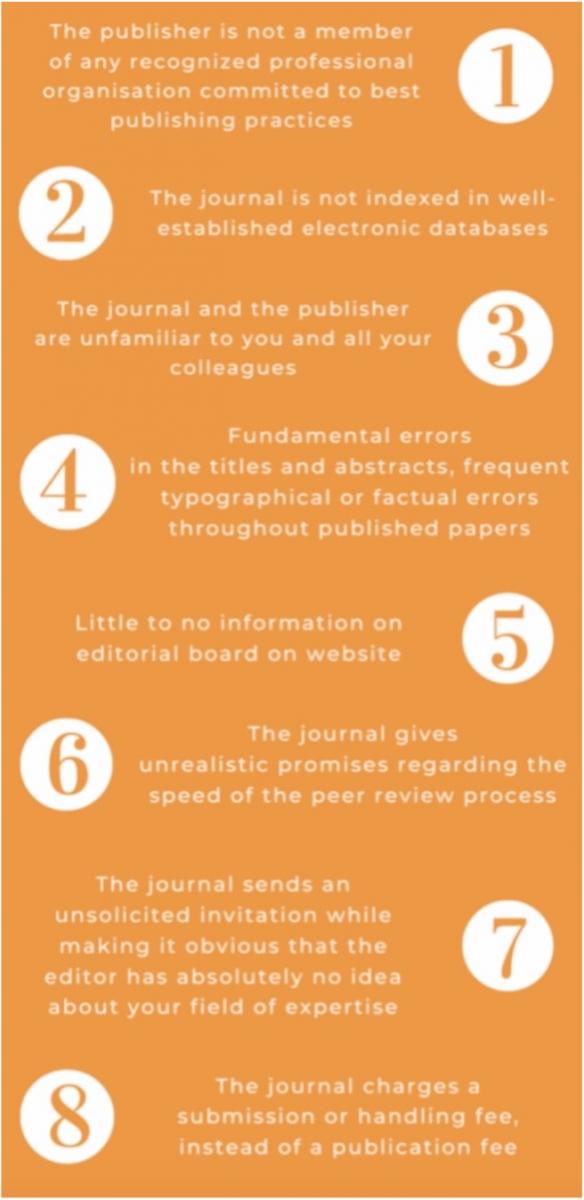

Figure 3: How to spot a predatory journal[6]

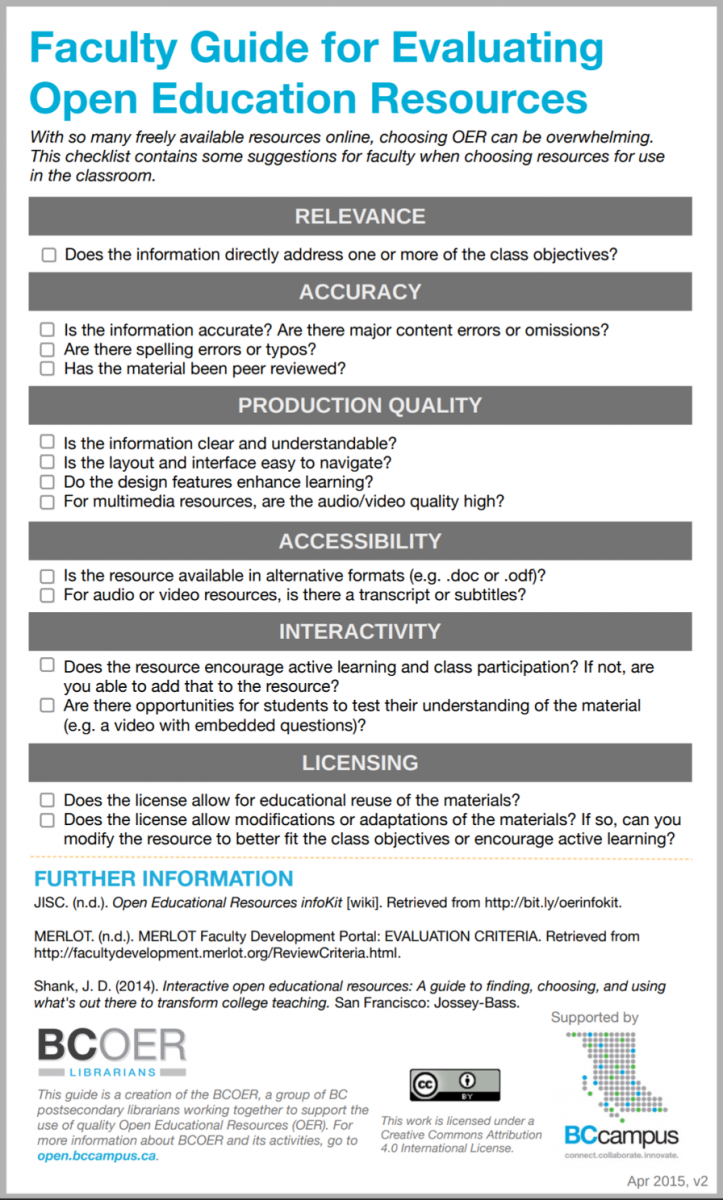

OER Africa has a free online tutorial on open access publishing, which includes suggestions on how to verify a journal’s legitimacy.[7] There is also a discussion in Open Knowledge Primer for African Universities on the ways in which DOAJ tries to ensure that the journals in its database are legitimate.[8]

All researchers are under pressure to publish to keep their jobs and become eligible for promotion. The pressure on African scholars is increased because they cannot afford the high publication fees some journals charge, and some may not be familiar with the steps necessary to evaluate journals.

Two researchers are quoted in a 2022 article in the Africa Edition of University World News to illustrate the dilemmas facing African scientists who must publish but have neither the funds to pay the APC costs of top-tier journals nor the knowhow to discern the legitimate from the predatory.[9]

One scientist, Euclides Sacomboio of Agostinho Neto University in Angola, had two articles published in disreputable journals. His preference would have been high-impact journals, but, as he told University World News:

"I earn US$500, and the article processing fee in reputable journals is about US$2,180. Where do I get the money without any support?"

Sacomboio added:

"To me, it was important to share my data. Worse, it was difficult to choose [where to publish] because some of these journals we call predatory have peer review processes."

The second scientist, Moses Samje of the University of Bamenda, Cameroon and a member of the African Academy of Sciences Chapter of Affiliates, was also taken in—this time because the journal’s focus was on research like his and because of the journal’s allegedly high impact factor. Samje said:

"The impact factor was quite attractive. It was too good to be true … We had to try and we submitted a paper and, in the space of 24 hours, they [the publishers] asked for the processing charge, which was getting way more affordable. In less than 48 hours, we received an e-mail [saying] our paper was online. I was quite excited."

Samje subsequently went online and discovered that the journal’s peer review process was not as it seemed; he believes that the journal is a sham.

‘Plagiarism, fraud, and predatory publishing’

The noted bioethicist, Arthur Caplan, wrote those words in 2015 and called predatory journals ‘polluting journals.’[10]

Although the points in figure 3 elucidate the major ways to identify a predatory journal, there are two additional strategies they employ. Predatory journals are noted for accepting plagiarized articles and those that have already been published elsewhere. Even though predatory journals may report that they check for plagiarism, they typically don’t.

A 2018 blog post in the Indian newsletter, The Wire, succinctly described the situation in India and gave examples. The authors wrote:[11]

"Fake journals and plagiarism in academics go hand-in-hand. The lack of peer review and a complete absence of quality checking provides a safe channel to publish plagiarised articles. It is therefore no coincidence that along with fake journals, almost all academic fields have also seen an epidemic of plagiarism."

Sometimes plagiarism is intentional; other times it is the result of a researcher’s lack of expertise on what the concept means.

It isn’t always easy to find specific examples of plagiarism. Science Integrity Digest is one source of information. In 2020, it reported on a clear case of plagiarism in which the work of the OstrowskiLab was stolen and published in a predatory journal.[12] In 2019 in the Journal of Nursing Scholarship, authors wrote about numerous instances of plagiarism in three predatory nursing journals.[13]

In South Africa, Professor Nicki Tiffin, a former researcher at the University of Cape Town (UCT) found that not only had she been plagiarized in a predatory journal, but her name had been stolen too.[14]

Unwary researchers are also trapped because some predatory journals have titles very similar to those of reputable journals. The three journals in the figure below all have similar titles but the similarity ends there.

What's in a name?

The first journal, Plant Physiology and Biochemistry is published by Elsevier, a reputable scientific publisher. The second, Journal of Plant Biochemistry and Physiology, is published by Longdom Press. Note it has phone numbers in Great Britain and in Spain and a registered address in Brussels. The journal is not included in any of the major indexing services that have quality controls, such as Web of Science, Scopus, or PubMed. The third, Journal of Plant Biochemistry & Physiology, is published by Omics, a publisher that was sued by the US Federal Trade Commission for predatory practices and ordered to pay a fine of more than $50 million.[15]

How to help researchers distinguish between the fake and the real

Above, we outlined several ways to determine legitimate journals from predatory ones. The two OER Africa publications we cited offer detailed help to students, researchers, and librarians.

Intellectual property rights, plagiarism, and referencing are taught in the Use of Libraries or embedded in the Use of English course, which is an integral part of the compulsory General Studies (GS) for first year students in Nigerian universities. However, the effect of the course on students has been found to be minimal.[16] Traditionally, African academic libraries run library orientation activities for new students. This window of opportunity could be widened to include provision of information packs or tutorials (online and physically) on information literacy, copyright, and plagiarism issues (including an introduction to plagiarism detecting software), as well as information about predatory journals.

Figure 4: AfLIA poster for use in libraries

Academic libraries can play an important role in raising awareness to the need to be wary of predatory practices. But universities as a whole should be engaged in preventing staff and students from falling prey to these journals. They can list the open access journals for which academics associated with their institution can use for purposes of promotion, tenure, and contracts. The DHET site discussed above would be a good place start. Supervisors can advise their PhD students about conducting a literature review without including predatory journals. Sarah Elaine Eaton of the University of Calgary wrote the following about the need of universities to support their students and academics against predation: [17]

"There are implications for mentors of graduate students and early-career stage academics, as well as for institutions as a whole. The issue of questionable conferences and publications is so complex that early-stage academics require support and mentorship to cultivate a deeper understanding of how to share their work in a credible way."

Dr. Eaton’s statement is valid around the world, particularly in circumstances such as Drs. Sacomboio and Samje described—insufficient funds to pay fees and insufficient guidance within the institution.

[1] See Sharing Africa’s knowledge through openly licensed publishing for more information on open access. https://www.oerafrica.org/content/sharing-africa’s-knowledge-through-openly-licensed-publishing

[3]See https://www.up.ac.za/news/post_3048195-the-department-of-higher-education-and-training-2022-accredited-journals-

[4]Grudniewicz, A., Moher, D., Cobey, K.D. et al. (2019). Predatory journals: no definition, no defence. Nature, Vol. 576: 210-212. Retrieved from https://media.nature.com/original/magazine-assets/d41586-019-03759-y/d41586-019-03759-y.pdf

[5]The Interacademy Partnership. (2022). Combatting Predatory Academic Journals and Conferences. Retrieved from https://www.interacademies.org/project/predatorypublishing

[6]European Pain Federation. (2021). How to Spot Predatory Journals. Retrieved from https://europeanpainfederation.eu/news/how-to-spot-predatory-journals/

[7]Lelliott, T. (2023). Publish Open Access revised. OER Africa. Retrieved from https://www.oerafrica.org/communication/publish-open-access/ - /

[8]Levey, L. (2023). Open Knowledge Primer for African Universities Revised and Updated Edition. Retrieved from https://www.oerafrica.org/system/files/12591/open-knowledge-primer-june-2023.pdf?file=1&type=node&id=12591

[9]Makoni, M. (2022). The battle against predatory academic journals continues. University World News. Retrieved from https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20221213224021432

[10]Caplan, A.L. (2015). The Problem of Publication-Pollution Denialism. Mayo Clinic, Vol 90(5):565-566. Retrieved from https://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org/article/S0025-6196%2815%2900190-1/pdf

[11]Raniwala, R. and Raniwala, S. (2018). 'Predatory' Is a Misnomer in the Unholy Nexus Between Journals and Plagiarism. Retrieved from https://thewire.in/the-sciences/predatory-journals-fake-journals-plagiarism-peer-review-mhrd-ugc

[12]Bik, E. (2023). Investigation finds ‘egregious misconduct’ by CUNY scientist. Retrieved from https://scienceintegritydigest.com/2020/07/28/plagiarism-in-chemistry-a-case-report/

[13]Owens, J.K. and Nicoll, L.H. (2019). Plagiarism in Predatory Publications: A Comparative Study of Three Nursing Journals. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, Vol. 51(3):356-363. Retrieved from https://sigmapubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jnu.12475 - :~:text=This focused study has clearly,evidence accurately to inform practice.

[14] Simon, N. (2023). Protecting research integrity from predatory journals. University of Cape Town. Retrieved from https://www.news.uct.ac.za/article/-2023-11-09-protecting-research-integrity-from-predatory-journals

[15]Federal Trade Commission. (2019). Court Rules in FTC’s Favor Against Predatory Academic Publisher OMICS Group; Imposes $50.1 Million Judgment against Defendants That Made False Claims and Hid Publishing Fees. Retrieved from https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2019/04/court-rules-ftcs-favor-against-predatory-academic-publisher-omics-group-imposes-501-million-judgment

[16] Ogunmodede, T. A., Adio, G. and Odunola, O. A. (2011). Library Use Education as a Correlate of Use of Library Resources in a Nigerian University. Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). Vol.604. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/604

[17] See Sarah Elaine Eaton’s Resource Guide Avoiding Predatory Journals and Questionable Conferences. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED579189.pdf

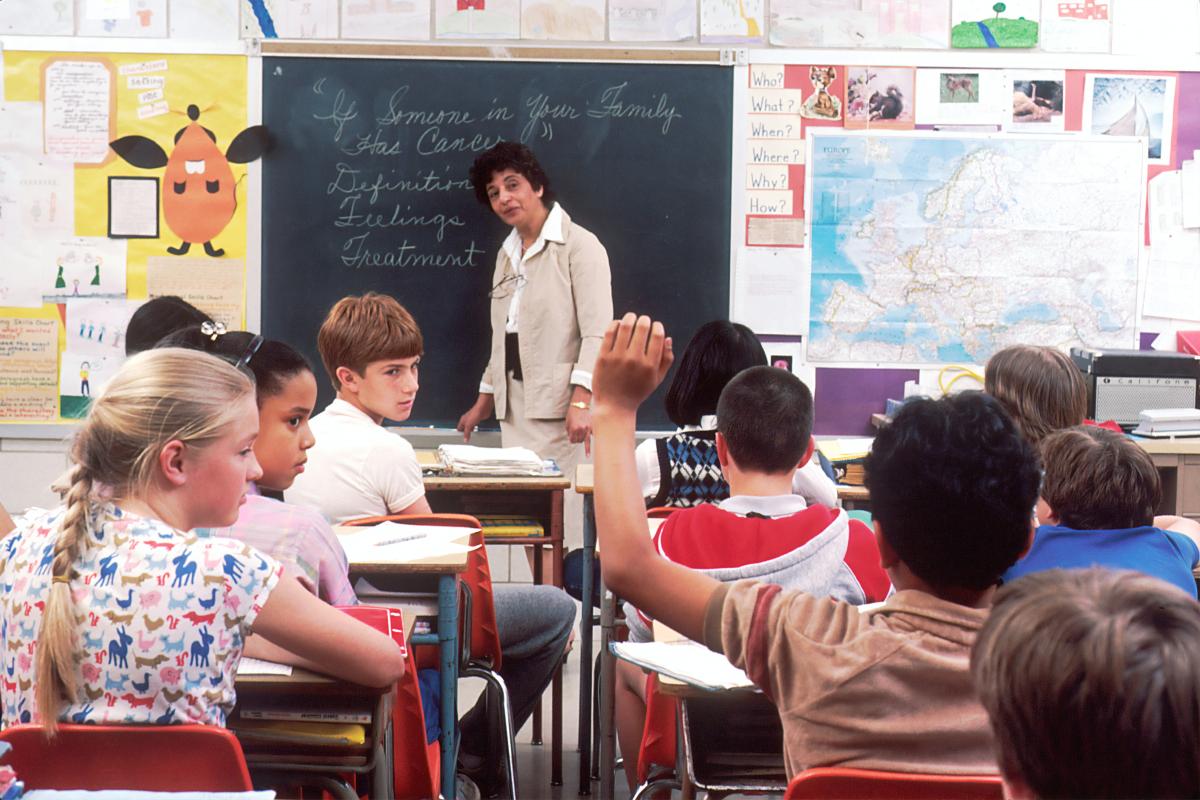

Education systems around the world have traditionally been characterized by closed knowledge systems, overly prescriptive curricula, narrow conceptions of success, and a failure to fully empower teachers as facilitators of learning. A recent paper by Neil Butcher & Associates argues that a key reason for these issues is that many education systems are inhibited by complex policy environments that, likely unintentionally, impede learning and create educational closure.

Image courtesy of Michael Anderson, Unsplash, Unsplash licence

Education systems around the world have traditionally been characterized by closed knowledge systems, overly prescriptive curricula, narrow conceptions of success and achievement, and a failure to fully empower teachers as facilitators of learning. This inhibits their ability to develop a full spectrum of human learning capabilities amongst learners, especially in their formative schooling years. A recently published paper by Neil Butcher & Associates (NBA) argues that, while there may be various reasons for these issues, one critical problem is that many education systems are inhibited by complex policy environments that, most likely unintentionally, impede meaningful learning and create educational closure.

Education policies often create new rules that accumulate over time, giving rise to inefficiencies and unnecessary constraints that do not support (and often obstruct) learner success. One manifestation of policy complexity within education systems is the growing granularization and rigidity of the formal national curriculum, which has led to the proclivity to use standardized testing and high-stakes examinations as a proxy for learner success. This complexity has also eroded autonomy for teachers, constraining what they can do in the classroom and increasing the tendency to ‘teach to the curriculum’ (or, worse even, to the examination). Standardized testing and high-stakes examinations have also increased anxiety and tension amongst learners, parents, and teachers, who perceive a false equivalence between test performance and success in later life.

The paper argues that despite the diverse nature of education systems around the world, many share a common problem of complex policy environments. Increased use of standardized testing models and resulting curriculum rigidity does not lead to better quality education but can have a deleterious effect on learner achievement. As complexity filters down into the classroom, another consequence is that the teachers who are tasked with delivering curricula are increasingly constrained and disempowered by these central policies. The consequences of this are far reaching as they emphasize rigidity and closure in knowledge acquisition, leaving little space for substantive learner-teacher engagement, contextual adaptation, and discovery.

In response to these challenges, we can use the principles of open learning as a tool to reflect on policy complexity in education systems, including the extent to which a policy environment is facilitating openness or promoting closure. A useful mechanism to tackle policy creep and ensure that education systems are geared toward a broader definition of learner success is to adopt and systematically implement the concept of openness within education systems, which begins at the policy level. Prioritizing openness offers significant opportunities for teachers and learners to reclaim what happens in the classroom and become more engaged members of society.

Integrating open learning principles into policy discourse would be a step forward in reducing unnecessary complexity and closure within education systems.

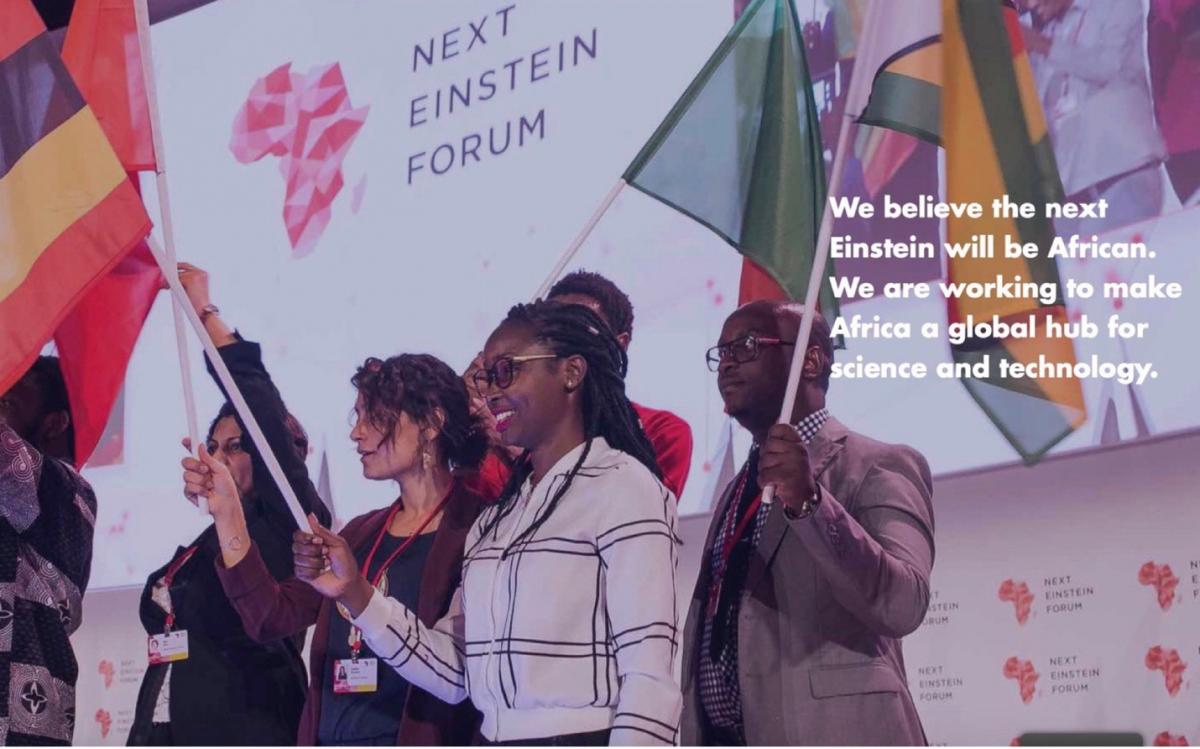

African languages are vastly underrepresented in the global knowledge pool, even though scholars at Harvard University believe that Africa is home to about one third of the world’s languages. This week, we delve into how Artificial Intelligence can assist with African language representation, and some of the challenges therein.

Much has been written about Artificial Intelligence (AI), mainly in English, including by OER Africa.[1] English is the predominant language on the Internet, in research and publications, and in education. African languages are vastly underrepresented in the global knowledge pool, even though scholars at Harvard University believe that with between 1,000 and 2,000 languages, Africa is home to about one third of the world’s languages.[2]

Artificial intelligence (AI) can play an important role in mitigating these language challenges. Already, international search engines, such as Google, play a large role in using AI to translate English into African languages and vice-versa. Efforts are constrained, however, by the paucity of documents on the web written in most African languages. Additionally, networks of African researchers have become actively engaged in looking for ways to increase the data on the web in African languages, including documenting scientific terms in the African languages where no such terms currently exist. Such data will then be available for use by AI to improve access to African languages. Importantly, they are trying to grow the field of African AI researchers by building networks and finding AI language technology solutions.

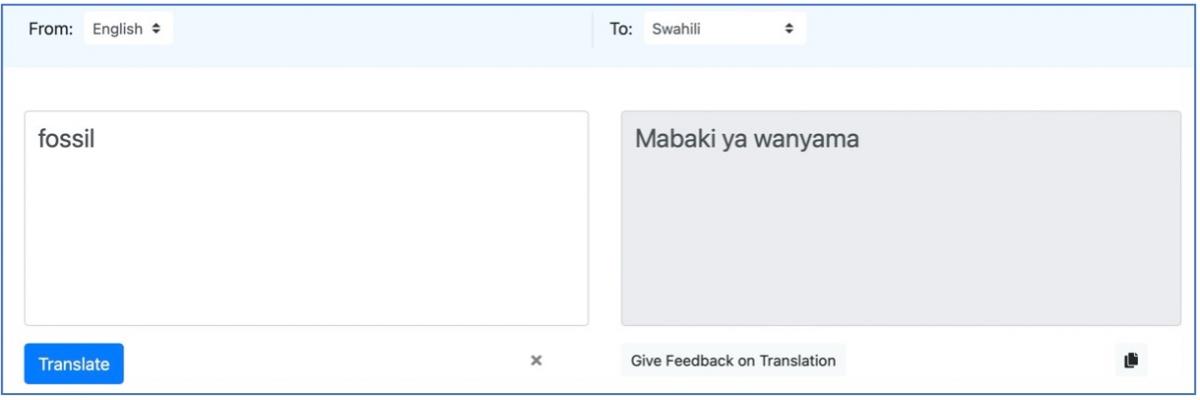

Many of us think about Google Translate when we want to understand what has been written in a language that we do not understand. Google Translate is now supported in 25 African languages: Afrikaans, Amharic, Arabic, Bambara, Chichewa, Ewe, Hausa, Igbo, Kinyarwanda, Krio, Lingala, Luganda, Malagasy, Oromo, Sepedi, Swahili, Sesotho, Shona, Somali, Tigrinya, Tsonga, Twi, Xhosa, Yoruba, and Zulu. Several of these languages are spoken across borders. The good news is that the number of them keeps increasing. The bad news is that there does not seem to be any one place to ascertain which African languages are covered; this can only be determined through searches within Google Translate. Furthermore, Google Translate uses machine translation, which is mostly accurate, but not entirely.

The Nigerian linguist, Aremu Adeola, uses an interesting example about why context matters in many languages, including Yoruba:[3]

"Most translations done by machines render some words wrong, especially words that are culturally nuanced. For example, Yorùbá words ayaba and obabìnrin have their meanings situated in a cultural context. Most machines translate both words as ‘queen.’ However, from a traditional-cum-cultural vantage point, it is essential to note that the meanings of ayaba and obabìnrin are different: Ọbabìnrin means ‘queen’ in English while ayaba is ‘wife of the king.’"

Using AI as a translation tool is not straightforward. Most AI tools:[4]

"Rely on a field of AI called natural language processing, a technology that enables computers to understand human languages. Computers can master a language through training, where they pick up on patterns in speech and text data. However, they fail when data in a particular language is scarce, as seen in African languages."

The South African science journalist, Sibusiso Biyela, gives an excellent example of just how difficult it can be to make scientific discoveries understandable and relatable in African languages, such as isiZulu. Biyela was given an assignment to write about the discovery of a new species of dinosaur, Ledumahadi mafube in isi-Zulu. He explained:[5]

"But there’s no word for “dinosaur” in Zulu. Nor are there words for “Jurassic,” “fossilization,” or “evolution.” Despite the fact that Zulu—or isiZulu, as the language is called in South Africa—is spoken by some 10 million people, it simply doesn’t have the words for communicating science.

So my news piece wasn’t just a news piece. It was an attempt to tell a science story in a language that science overlooked—to help right a societal wrong. It was a small contribution among an increasing number that aim to help decolonize South African science writing. And it was rife with more pitfalls than I could have imagined. The task of describing science clearly, concisely, and accurately—already challenging in English—became exponentially more difficult in my native tongue."

At the end of his article, Biyela gives a lexicon of some of the English-isiZulu scientific terms that he used. Biyela uses technology joined with his expertise in science for his work on conveying scientific terms from English to isiZulu. He was one of the partners in Masakhane, which is discussed below.[6]

The underrepresentation of African languages online makes it more difficult to use AI as a translating tool because computers have trouble identifying datasets with which to work. Several organizations are trying to mitigate this challenge, among them the Masakhane Research Foundation. Masakhane is collaborating with the African scientific preprint server, AfricArXiv,[7] to find a way to translate the papers that AfricArXiv receives into African languages.

Masakhane is a grassroots natural language processing (NLP) network that was formed for NLP research in African languages, for Africans, by Africans. The Masakhane community consists of:[8]

">1000 participants from 30 African countries with diverse educations and occupations, and >3 countries outside Africa. As of February 2020, over 49 translation results for over 38 African languages have been published by over 35 contributors on GitHub."

Masakhane has a trial translation page, but the translation results do not always match those of Google Translate. For example, ‘kisukuku’ is how ‘fossil’ is translated in Google Translate. ‘Mabaki ya Wanyama’ is the translation given by Masakhane. (Most online translations use kisukuku).

Figure 1: What is the correct translation?

These efforts are just getting started. If Africa is going to join the global knowledge pool, its languages must be represented too. Both AfricarXiv and Masakhane welcome volunteers; there are other such organizations that would also appreciate assistance.

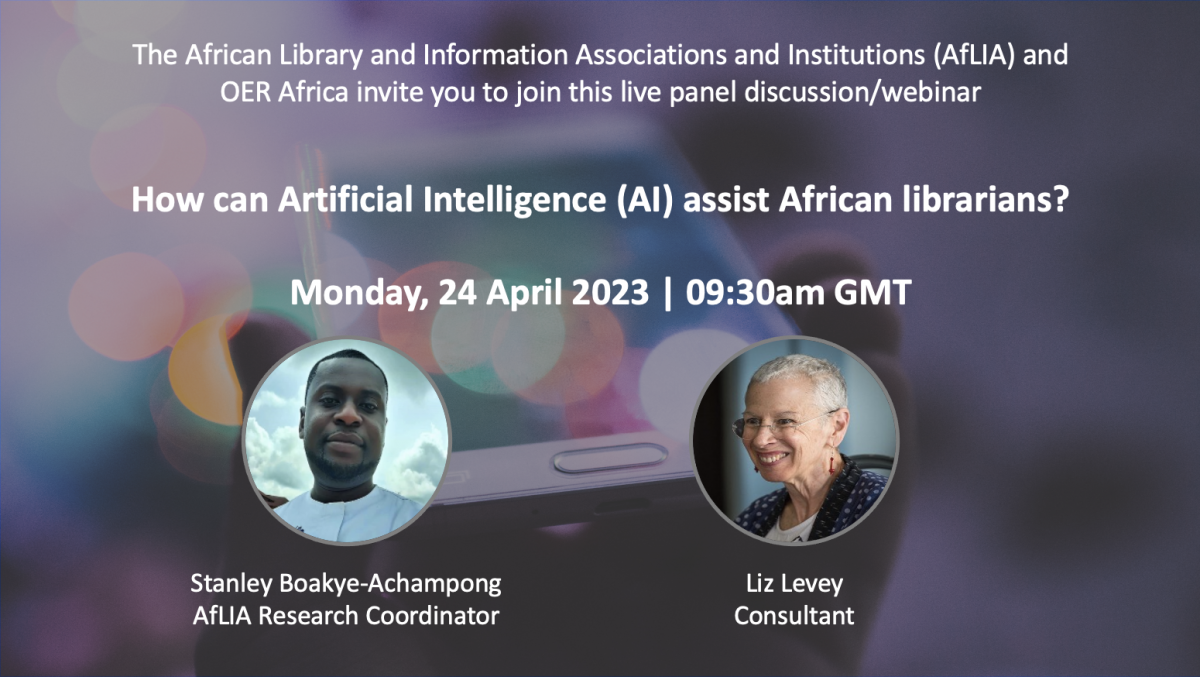

And for those who are interested in the interrelationship between AI and library and information studies, the African Library and Information Associations and Institutions (AfLIA) will host a webinar on this topic on 25 October 2023. Visit the webinar’s information page for more information.

Related articles

- Three ways Artificial Intelligence could change how we use Open Educational Resources

- Where does ArXiv fit into Open Science? But first, how do I pronounce it?

- Panel Discussion: How can AI assist African Librarians

References and attribution

[1] July 28, 2023 https://www.oerafrica.org/content/three-ways-artificial-intelligence-could-change-how-we-use-open-educational-resources

[2] https://alp.fas.harvard.edu/introduction-african-languages - :~:text=With anywhere between 1000 and,third of the world%27s languages.

[3]Lost in Translation: Why Google Translate Often Gets Yorùbá-and Other Languages-Wrong. Aremu Adeola. Rising Voices. 20 November 2020. https://rising.globalvoices.org/blog/2020/11/20/lost-in-translation-why-google-translate-often-gets-yoruba-and-other-languages-wrong/

[4] A roadmap to help AI technologies speak African languages. 11 August 2023. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2023/08/230811115430.htm

[5] Decolonizing Science Writing in South Africa. Sibusiso Biyela. 12 February 2019. https://www.theopennotebook.com/2019/02/12/decolonizing-science-writing-in-south-africa/

Image at the top of the article courtesy of albyantoniazzi, Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA

From 4 to 7 September 2023, we celebrate the inaugural Digital Learning Week – a reframing of what was previously known as Mobile Learning Week. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) will convene in-person events for policymakers, practitioners, educators, private sector partners, researchers, and development agencies.

Image courtesy of Siphosihle Mkhwanazi, Wikimedia (CC BY-SA)

This week, we celebrate the inaugural Digital Learning Week – a reframing of what was previously known as Mobile Learning Week. From 4 to 7 September 2023, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) will convene in-person events for policymakers, practitioners, educators, private sector partners, researchers, and development agencies.

Under the theme ‘Steering technology for education’, the event will explore public digital learning platforms and generative AI, examining how both can be steered to reinforce and enrich humanistic education.

Plenary sessions, panel discussions and public lectures will be livestreamed. The full programme, including links to each session, is available here.

Some highlights to look forward to include:

- Release of Guidance for Generative AI in education and research

- Presentation of AI Competency Frameworks for Students and Teachers

- Release of UNESCO policy guidelines on digital learning and AI in education, including AI and Education: Guidance for Policymakers, Guidelines for ICT in Education Policies and Masterplans, Education and Blockchain, and K-12 AI curricula: a mapping of government-endorsed AI curricula

- Progress report on Gateways to Public Digital Learning

For more information, visit the Digital Learning Week page.

Related articles

In August 2023, the African Library and Information Associations and Institutions (AfLIA) and Neil Butcher & Associates (NBA) co-published an Overview for African Librarians on the UNESCO OER Recommendation and Open Knowledge.

A William and Flora Hewlett Foundation grant to NBA funded the research and writing entailed in producing the Overview.

Figure 1: AfLIA poster on the UNESCO OER Recommendation

The UNESCO Recommendation on Open Educational Resources (OER) is significant to all those who are interested in and committed to ensuring that all learners have access to appropriate high-quality educational content, including librarians. It was approved unanimously by UNESCO member states in November 2019.

In August 2023, the African Library and Information Associations and Institutions (AfLIA) and Neil Butcher & Associates (NBA) co-published an Overview for African Librarians on the UNESCO OER Recommendation and Open Knowledge.[1] A William and Flora Hewlett Foundation grant to NBA funded the research and writing entailed in producing the Overview.

The Overview explores how the OER Recommendation’s five action areas are relevant to librarians and what librarians can do to support their implementation. It examines how the OER Recommendation relates to the different library types in Africa and the user communities the libraries represent.

It further aims to help African librarians develop a deeper understanding of OER, including the kinds of open content that will resonate with library users. OER is consonant with other equally important principles for librarians—access to equitable, suitable, and relevant content for easy sharing and interoperability of knowledge within Africa. All these facets are included in the Overview.

The Overview is filled with insights and stories from librarians on open knowledge and open licensing, including how traditional knowledge, culture, and languages can be used in creating and adapting openly licensed content.

AfLIA also produced a comic strip to explain to librarians why OER and UNESCO’s OER Recommendation are so important. Comic strips on teaching are becoming increasingly popular; Google has a full page of images, as does OER Commons. But we could not find a comic strip to explain open licensing or OER…until AfLIA came along and created one.

If you would like more information on the Overview or would be interested in joining related discussions, please write to Nkem Osuigwe, AfLIA’s Director of Human Capacity Development and Training. Her email address is neosuigwe@aflia.net.

Figure 2: AfLIA poster on collecting and opening up Africa's heritage

Related articles

- Opening education: What role do librarians on the African continent play?

- The Revised Open Knowledge Primer for African Universities

- How can we plan professional development in universities?

- Reinvigorating libraries: South African Library Week 2022

[1] The document is available on both the AfLIA and NBA websites: https://web.aflia.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/UNESCO-OER-Recommendation-Overview-for-librarians-_230802_093332.pdf and https://www.nba.co.za/resource/unesco-oer-recommendation-and-open-knowledge-overview-african-librarians

Over the past year, news about Artificial Intelligence (AI) has abounded. Information about breakthroughs and new applications have become commonplace, and we have been thrust into a world where AI-enabled technologies are starting to change how we work and live.

In this article, we consider three ways that AI might change how we use OER.

Introduction

Over the past year, news about Artificial Intelligence (AI) has abounded. Information about breakthroughs and new applications have become commonplace, and we have been thrust into a world where AI-enabled technologies are starting to change how we work and live. For better or for worse, we have ushered in the era of AI.

Many are asking what the implications of this might be for the education sector. Will it affect teaching and learning positively or negatively? How can AI-enabled technologies personalize education – and will this be educationally beneficial? What organizations are already working on AI in education and how, if at all, is this work regulated? An air of uncertainty pervades the sector in terms of the benefits and risks of harnessing AI in education.

At OER Africa, we have written extensively on how Open Educational Resources (OER) might improve aspects of education, including access, relevance, and quality. Likewise, the intersection of OER and AI necessitates greater exploration, particularly given the opportunities that it offers to scale access to high quality education.

In this article, we consider three ways that AI might change how we use OER.

How AI could change our engagement with OER

1. OER Content Development

AI tools can be used to develop new OER using natural language processing and machine learning capabilities. They might be able to help educators create interactive learning materials, assessments, and learning simulations, expanding the range of available OER and enabling novel teaching practices.

One of the most popular platforms that demonstrates such capabilities is ChatGPT (or Chat Generative Pre-Trained Transformer), an AI chatbot developed by OpenAI. Since its release in November 2022, is has amassed over 100 million users.

There is no doubt that generative tools like ChatGPT hold great potential to save time and effort for OER creators. With a few well-crafted prompts, ChatGPT can: generate thousands of words on a subject; create dozens of sample questions that could be included in an open textbook for learners to be able to self-evaluate their own learning; create lesson plans and assignments; and develop question prompts that can be used as asynchronous discussion prompts in discussion forums.[1] However, it is crucial that OER creators use their own expertise to check that what is generated by ChatGPT is indeed correct.

For educators working with OER, copyright ownership of AI-generated works is important to determine as, by definition, OER are materials unencumbered by legal restrictions that may prevent the reuse, sharing, redistribution, and adaptation of copyrightable works. While some are using the rise of generative AI to question the validity of copyright itself, the question of who owns the copyright when a work is created by AI is a very murky area, both legally and ethically.[2,3] When we asked ChatGPT whether the content it produces is openly licensed, it had the following to say:

As of my last update in September 2021, the content generated by ChatGPT and similar AI language models is not openly licensed. AI language models, including ChatGPT based on the GPT-3.5 architecture, are proprietary technologies developed by organizations like OpenAI.

…Therefore, when using content generated by ChatGPT or any other AI language model, it is essential to review the terms of service, usage policies, and any specific guidelines provided by the organization that owns the AI model to ensure compliance with their requirements.

It's worth noting that the field of AI and its legal and ethical implications are continually evolving, and there might be changes or developments in the licensing and usage of AI-generated content beyond my last update. I recommend checking with the organization that provides the AI service for the most current and accurate information regarding the licensing and usage of their AI-generated content.[4]

We recommend that users of these technologies stay abreast of these kinds of debates, read terms of service of the organizations that create these technologies, pay close attention to licensing conditions, and state clearly when they have used AI tools to generate intellectual property.

2. Personalized Learning

Some AI algorithms can develop tailored recommendations for OER based on a learner's performance, learning preferences, and development areas. This implies that learners can use OER that meet their requirements, making the learning pathway more engaging and effective.

For example, Siyavula is a South African organization that provides personalized and adaptive learning platforms. Siyavula has produced book titles from Grades 4-12. These are high quality OER that are aligned with the South African curriculum for mathematics, physics and chemistry. Learners can now also access Siyavula’s adaptive learning software, which adjusts the difficulty levels of exercises through machine learning to cater to each learner’s individual needs.[5]

3. Translation and Localization

AI can enable translation and localization of openly licensed content. Software with machine translation capabilities, such as Google Translate, can translate OER into different languages, facilitating knowledge sharing. It is always recommended that users state when they have used these kinds of tools for translation purposes.

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) has been exploring the use of AI for the translation and localization of educational content. It has collaborated with partners to develop machine translation systems and tools that bridge language gaps in accessing OER. For example, the Global Digital Library (GDL) collects existing high-quality openly licensed reading resources and makes them available on the web, mobile and for print. The platform also supports translation and localization of GDL-resources to more than 300 languages. UNESCO partnered with the GDL team under the auspices of the Norwegian Programme for Capacity Development in Higher Education and Research for Development (known as NORAD) and the Global Book Alliance to launch the GDL in Asia. Reading materials in 41 Asian languages, including seven Nepali languages were launched.[6]

Despite the benefits of integrating AI into OER, there are several potential challenges and concerns. For example, the issue of data privacy has received a lot of attention recently, as the use of AI algorithms often entails the collection and analysis of user data. Ensuring that such data is stored securely and used responsibly is critical to maintaining the trust and privacy of both learners and educators.[7]

A second challenge is the potential for AI to exacerbate existing inequalities in education. As AI-powered OER become more widespread, there is a risk that those who cannot access such resources or platforms may be left behind due to unstable internet connections for example. There may also be inherent biases in the data that is used to train AI models, such as a lack of data from Sub-Saharan African countries. Thus, introducing measures to ensure that AI-driven educational tools are accessible to learners regardless of their geography or socioeconomic contexts is key to promoting educational equity.[8]

Conclusion

Regardless of one’s outlook on the impact that AI could have on society over time, its integration into most spheres of our lives in some shape or form is progressing fast. With regard to OER, AI offers exciting opportunities to augment the production, dissemination, and access to quality educational resources. However, rolling out such capabilities means that we need to consider potential shortfalls, including that we might inadvertently inhibit access to such platforms for those who face educational barriers.

Some further reading on this topic:

- Lalonde, C. (2023). ChatGPT and Open Education. BC Campus. Available at: https://bccampus.ca/2023/03/06/chatgpt-and-open-education/

- Downes, S. A look at the future of Open Educational Resources. An Introduction to Open Education. Available at: https://edtechbooks.org/open_education/a_look_at_the_future

- Wiley, D. AI, Instructional Design, and AI. Improving Learning. Available at: https://opencontent.org/blog/archives/7129

Related articles in OER Africa’s archive

- Artificial Intelligence and African Librarians

- Protecting personal information when using and distributing OER

[1] Lalonde, C. (2023). ChatGPT and Open Education. BC Campus. Retrieved from: https://bccampus.ca/2023/03/06/chatgpt-and-open-education/

[2] Lalonde, C. (2023). ChatGPT and Open Education. BC Campus. Retrieved from: https://bccampus.ca/2023/03/06/chatgpt-and-open-education/

[3] See article here

[4] Conversation with ChatGPT on 24 July, 2023. OpenAI's ChatGPT, based on the GPT-3.5 architecture.

[5] See article here

[6] See article here

[7] Frackiewicz, M. (2023). AI in Robotic Open Educational Resources. Retrieved from https://ts2.space/en/ai-in-robotic-open-educational-resources/#:~:text=AI%2Dpowered%20chatbots%2C%20for%20instance,thinking%20and%20problem%2Dsolving%20skills.

[8] Frackiewicz, M. (2023). AI in Robotic Open Educational Resources. Retrieved from https://ts2.space/en/ai-in-robotic-open-educational-resources/#:~:text=AI%2Dpowered%20chatbots%2C%20for%20instance,thinking%20and%20problem%2Dsolving%20skills

OER Africa has just published an expanded and revised 'Open Knowledge Primer for African Universities.' In the five years since we wrote the first edition, open education has now grown to include developments in open access, open data, open educational resources (OER), and open science. We thought it was time for a refresh.

The image above is taken from Next Einstein Forum

OER Africa has just published an expanded and revised Open Knowledge Primer for African Universities. In the five years since we wrote the first edition, open education has now grown to include developments in open access, open data, open educational resources (OER), and open science. We thought it was time for a refresh.

This new primer includes sections on how open access has changed to include more journals and publication mechanisms, new requirements for making data open, and how OER fits into open access. Librarians play a key role in promoting information literacy for students and staff; we have added sections specifically for them. There is also a new section on information resources, subdivided by subject. We have broadened the section on impact factors to explain why researchers in the global South are affected deleteriously by them.

This primer has grown considerably since the first edition. Although you can read it from cover to cover, it might also be useful to keep it handy as a reference document and read sections when you have need of specific information.

We welcome your comments, including on areas where we are not clear or that require expansion. Please email levey180@gmail.com.

The primer can be found here.

Funded by The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Saide OER Africa embarks on an impactful project to support the effective development and use of Open Education Resources in higher education systems in selected sub-Saharan African countries. Ashton Maherry, reports on recent travels to Beira, Mozambique, to establish a strategic partnership with UnISCED.

Figure 1: Representatives from OER Africa and UnISCED

As part of Saide’s OER Africa initiative, Ashton Maherry (Saide) and Neil Butcher (Neil Butcher & Associates) recently visited UnISCED to establish a partnership to promote the use of Open Education Resources (OER) at UnISCED. UnISCED (translated as Open University Institute of Sciences and Distance Education) is a Mozambican private higher education institution dedicated exclusively to open and distance education and was established in 2014.

The current William and Flora Hewlett Foundation grant in support of OER Africa, continues its focus of supporting effective development and use of OER in higher education systems in African universities. The project has four outcomes:

1. Development of comprehensive Continuous Professional Development (CPD) Frameworks for academics, senior management and academic librarians.

2. Development of an online collection of Continuous Professional Development Open Education Resources in higher education

3. Collaboration with at least four African universities

4. Establishment of a Continuous Professional Development network

The visit to UnISCED forms part of a planned collaboration with at least four Universities including, Botswana Open University, the University of Namibia and UnISCED and hopefully one other, still to be determined.

Several areas of the strategic partnership were identified during the UnISCED visit, these include the development, implementation and evaluation of policies that support the use of OERs, capacity building of senior management, academics and academic librarians to use OERs to strengthen teaching and learning, the identification of possible free or commercial online resources that can help academics with their teaching and learning materials, such as simulators and virtual labs, and the exciting challenge of translating predominantly English resources to Portuguese. In addition, the possibility of UnISCED becoming a member of the African Association of Librarians (AfLIA) was explored and will be taken forward in the next three months.