Friday, 28th July 2023

Introduction

Over the past year, news about Artificial Intelligence (AI) has abounded. Information about breakthroughs and new applications have become commonplace, and we have been thrust into a world where AI-enabled technologies are starting to change how we work and live. For better or for worse, we have ushered in the era of AI.

Many are asking what the implications of this might be for the education sector. Will it affect teaching and learning positively or negatively? How can AI-enabled technologies personalize education – and will this be educationally beneficial? What organizations are already working on AI in education and how, if at all, is this work regulated? An air of uncertainty pervades the sector in terms of the benefits and risks of harnessing AI in education.

At OER Africa, we have written extensively on how Open Educational Resources (OER) might improve aspects of education, including access, relevance, and quality. Likewise, the intersection of OER and AI necessitates greater exploration, particularly given the opportunities that it offers to scale access to high quality education.

In this article, we consider three ways that AI might change how we use OER.

How AI could change our engagement with OER

1. OER Content Development

AI tools can be used to develop new OER using natural language processing and machine learning capabilities. They might be able to help educators create interactive learning materials, assessments, and learning simulations, expanding the range of available OER and enabling novel teaching practices.

One of the most popular platforms that demonstrates such capabilities is ChatGPT (or Chat Generative Pre-Trained Transformer), an AI chatbot developed by OpenAI. Since its release in November 2022, is has amassed over 100 million users.

There is no doubt that generative tools like ChatGPT hold great potential to save time and effort for OER creators. With a few well-crafted prompts, ChatGPT can: generate thousands of words on a subject; create dozens of sample questions that could be included in an open textbook for learners to be able to self-evaluate their own learning; create lesson plans and assignments; and develop question prompts that can be used as asynchronous discussion prompts in discussion forums.[1] However, it is crucial that OER creators use their own expertise to check that what is generated by ChatGPT is indeed correct.

For educators working with OER, copyright ownership of AI-generated works is important to determine as, by definition, OER are materials unencumbered by legal restrictions that may prevent the reuse, sharing, redistribution, and adaptation of copyrightable works. While some are using the rise of generative AI to question the validity of copyright itself, the question of who owns the copyright when a work is created by AI is a very murky area, both legally and ethically.[2,3] When we asked ChatGPT whether the content it produces is openly licensed, it had the following to say:

As of my last update in September 2021, the content generated by ChatGPT and similar AI language models is not openly licensed. AI language models, including ChatGPT based on the GPT-3.5 architecture, are proprietary technologies developed by organizations like OpenAI.

…Therefore, when using content generated by ChatGPT or any other AI language model, it is essential to review the terms of service, usage policies, and any specific guidelines provided by the organization that owns the AI model to ensure compliance with their requirements.

It's worth noting that the field of AI and its legal and ethical implications are continually evolving, and there might be changes or developments in the licensing and usage of AI-generated content beyond my last update. I recommend checking with the organization that provides the AI service for the most current and accurate information regarding the licensing and usage of their AI-generated content.[4]

We recommend that users of these technologies stay abreast of these kinds of debates, read terms of service of the organizations that create these technologies, pay close attention to licensing conditions, and state clearly when they have used AI tools to generate intellectual property.

2. Personalized Learning

Some AI algorithms can develop tailored recommendations for OER based on a learner's performance, learning preferences, and development areas. This implies that learners can use OER that meet their requirements, making the learning pathway more engaging and effective.

For example, Siyavula is a South African organization that provides personalized and adaptive learning platforms. Siyavula has produced book titles from Grades 4-12. These are high quality OER that are aligned with the South African curriculum for mathematics, physics and chemistry. Learners can now also access Siyavula’s adaptive learning software, which adjusts the difficulty levels of exercises through machine learning to cater to each learner’s individual needs.[5]

3. Translation and Localization

AI can enable translation and localization of openly licensed content. Software with machine translation capabilities, such as Google Translate, can translate OER into different languages, facilitating knowledge sharing. It is always recommended that users state when they have used these kinds of tools for translation purposes.

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) has been exploring the use of AI for the translation and localization of educational content. It has collaborated with partners to develop machine translation systems and tools that bridge language gaps in accessing OER. For example, the Global Digital Library (GDL) collects existing high-quality openly licensed reading resources and makes them available on the web, mobile and for print. The platform also supports translation and localization of GDL-resources to more than 300 languages. UNESCO partnered with the GDL team under the auspices of the Norwegian Programme for Capacity Development in Higher Education and Research for Development (known as NORAD) and the Global Book Alliance to launch the GDL in Asia. Reading materials in 41 Asian languages, including seven Nepali languages were launched.[6]

Despite the benefits of integrating AI into OER, there are several potential challenges and concerns. For example, the issue of data privacy has received a lot of attention recently, as the use of AI algorithms often entails the collection and analysis of user data. Ensuring that such data is stored securely and used responsibly is critical to maintaining the trust and privacy of both learners and educators.[7]

A second challenge is the potential for AI to exacerbate existing inequalities in education. As AI-powered OER become more widespread, there is a risk that those who cannot access such resources or platforms may be left behind due to unstable internet connections for example. There may also be inherent biases in the data that is used to train AI models, such as a lack of data from Sub-Saharan African countries. Thus, introducing measures to ensure that AI-driven educational tools are accessible to learners regardless of their geography or socioeconomic contexts is key to promoting educational equity.[8]

Conclusion

Regardless of one’s outlook on the impact that AI could have on society over time, its integration into most spheres of our lives in some shape or form is progressing fast. With regard to OER, AI offers exciting opportunities to augment the production, dissemination, and access to quality educational resources. However, rolling out such capabilities means that we need to consider potential shortfalls, including that we might inadvertently inhibit access to such platforms for those who face educational barriers.

Some further reading on this topic:

- Lalonde, C. (2023). ChatGPT and Open Education. BC Campus. Available at: https://bccampus.ca/2023/03/06/chatgpt-and-open-education/

- Downes, S. A look at the future of Open Educational Resources. An Introduction to Open Education. Available at: https://edtechbooks.org/open_education/a_look_at_the_future

- Wiley, D. AI, Instructional Design, and AI. Improving Learning. Available at: https://opencontent.org/blog/archives/7129

Related articles in OER Africa’s archive

- Artificial Intelligence and African Librarians

- Protecting personal information when using and distributing OER

[1] Lalonde, C. (2023). ChatGPT and Open Education. BC Campus. Retrieved from: https://bccampus.ca/2023/03/06/chatgpt-and-open-education/

[2] Lalonde, C. (2023). ChatGPT and Open Education. BC Campus. Retrieved from: https://bccampus.ca/2023/03/06/chatgpt-and-open-education/

[3] See article here

[4] Conversation with ChatGPT on 24 July, 2023. OpenAI's ChatGPT, based on the GPT-3.5 architecture.

[5] See article here

[6] See article here

[7] Frackiewicz, M. (2023). AI in Robotic Open Educational Resources. Retrieved from https://ts2.space/en/ai-in-robotic-open-educational-resources/#:~:text=AI%2Dpowered%20chatbots%2C%20for%20instance,thinking%20and%20problem%2Dsolving%20skills.

[8] Frackiewicz, M. (2023). AI in Robotic Open Educational Resources. Retrieved from https://ts2.space/en/ai-in-robotic-open-educational-resources/#:~:text=AI%2Dpowered%20chatbots%2C%20for%20instance,thinking%20and%20problem%2Dsolving%20skills

What's New

Academic librarians can be at the forefront of helping users wade through the hyperbole, challenges, and benefits of AI. They have always been considered ‘the gatekeepers’ of knowledge. They can also open the door to better understanding of new technologies and concepts.

Image courtesy of Hal Gatewood, Unsplash

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has assumed a leadership role in discussions about education. Neil Butcher’s blog on AI’s false promises in education lays out major issues and pinpoints the easy assumptions on AI’s importance to educational systems.[1]

Academic librarians can be at the forefront of helping users wade through the hyperbole, challenges, and benefits of AI. They have always been considered ‘the gatekeepers’ of knowledge. They can also open the door to better understanding of new technologies and concepts.

African libraries have been trailblazers in adopting technology. In the 1990s, librarians in countries like Malawi, Ghana, and Nigeria were responsible for email in their institutions and countries. In those days, there was no viable Internet, and email was based on store and forward messaging. Emails would be stored on a computer system and then forwarded to the organization responsible for distributing them.[2]

Christine Kisiedu, then university librarian of the University of Ghana wrote:[3]

"It is often said that once ICT [Information and Communications Technology] development gets underway, it is unstoppable. This was certainly the case in Ghana. When a workshop on Electronic Networking for West African Universities (sponsored by the Association of African Universities and the American Association for the Advancement of Science) took place in Accra in December 1993, Ghana was not counted among the Internet savvy countries of the sub-region. Two years later, in 1995, a nationwide store-and-forward e-mail system had been established, and the first professional ISP in Ghana appeared on the scene and introduced Internet access to an interested but cautious Ghanaian public. In another year, development and patronage had reached such a level that Ghana could be said to be on the verge of an Internet explosion! Yet coming to grips with the new technology was not without its ups and downs.

…Learning to use the system proved more difficult than anticipated. I had just completed my second year as University Librarian at the Balme Library when we acquired e-mail…Nobody on the library staff had a clue as to how to operate this technology, much less how it worked. I submitted myself to a brief half hour’s explanatory session, which I must now publicly admit went in one ear and out the other. The consultant took too much for granted!"

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is the latest and trending ICT development, and again academic libraries are playing a leadership role.[4] The librarian of Northwestern University in the United States curates a page on the library platform on Using AI Tools in Your Research.[5] Other universities have done the same. A Google search for ‘library guides AI’ pulled up scores of university libraries offering AI guidance:

In a recent blog post on AI and educational technology, referred to above, Neil Butcher pointed to the disparities between what we know about AI and its impact on education. He emphasized that international groups like UNESCO are promoting AI’s success with little evidence to go on. Butcher wrote:[6]

"ChatGPT was only launched in November, 2022 but, by 2021, UNESCO had already launched a full publication entitled AI and Education that provides guidance to policy-makers. It seems a remarkable achievement that the world’s largest educational intergovernmental organization already felt confident enough in its understanding of the educational use of technologies about which we know so little and whose potential wider social impact is so little understood to offer unequivocal policy guidance on their use to governments. Having worked in educational policy for many years, my instinct is that it will be several years before we know enough about these issues to be clear about the policy implications."

The African Library and Information Associations and Institutions (AfLIA) and OER Africa decided to ask African academic librarians about their experiences and thoughts on AI. Nkem Osuigwe, AfLIA Director of Human Capacity Development and Training, put out a call on the AfLIA-OER Africa WhatsApp group. She wrote:[7]

"Have you ever noticed how technology seems to throw up opinions about the relevance of libraries?. Remember when the Internet went mainstream, and there were all sorts of permutations about the survival of libraries? Many asked if the Internet would replace libraries. When artificial intelligence became the new buzz concept, quite a number of librarians jumped in to talk about robots and what they can be used for in libraries.

Now, generative AI is the new rave. Young and old can do research on AI platforms, and within seconds, 'everything' is delivered, including references. Generative AI is creating art, writing essays, poems, short stories, drama, newspaper articles, and even social media posts.

Who needs libraries now, one may ask!. The verdict is not in yet. However, in Africa, we want to begin to tell our stories by ourselves about how libraries could use this technology so that we can 'own' the narrative about the tool.

• what impediments do we foresee in the advancement of AI?

• Can information literacy modules/classes and/or Use of Library courses introduce our users to 'ethical' AI?

• Can librarians assist in detecting when people are attributed for work by generative AI?

• Copyright and licensing issues are bound to crop up with the continued use of AI. Can African librarians help on creating awareness about this?

Generally, we’d love to hear about our interactions with AI as African librarian."

Librarian responses have been numerous and interesting. They are still coming in. Below are some examples of experiences reported:

The University of Ghana has revised its plagiarism policy to include use of AI:[8]

"Any employment of AI or associated technologies that compromises the authenticity of academic output will be deemed unacceptable,’ the document stated.

The University stresses originality in scholarly work, addressing AI's role in academic integrity.

The policy update underscores a commitment to ethical academic practices, leveraging technology while upholding original thought."

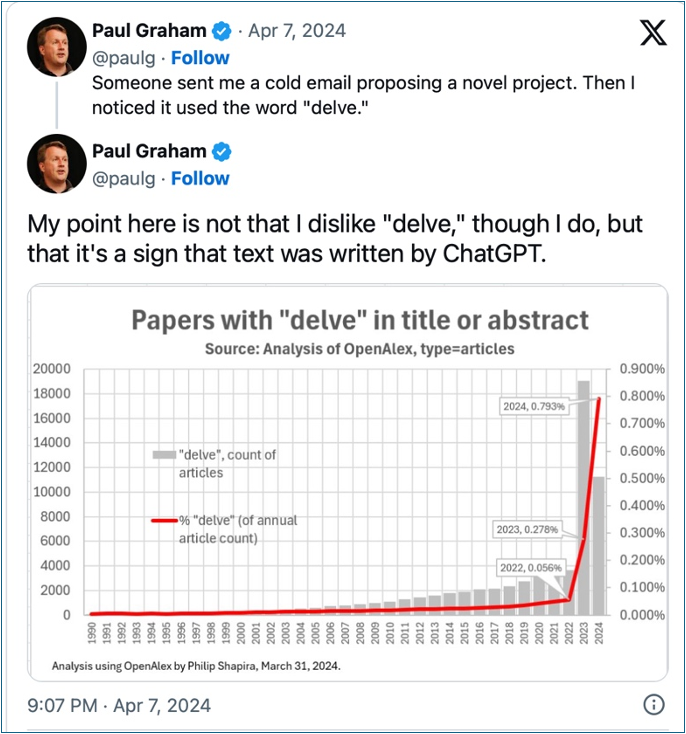

Researchers from the global South are accused of using AI if the language of their research papers and proposals use uncommon words like ‘delve’. One participant commented on vocabulary and AI:

"There was an uproar last week on Twitter. An American funder got a good project proposal, but ditched it because he saw the word 'delve' and thought the proposal was AI generated, because he doesn't write using these fancy words; only machines do.

Apparently, some words are already been termed AI generated words, and so AI detectors would look for such words and flag.

What happens when we use these words frequently in our write ups?"

The tweeter was Paul Graham, co-founder of Y-Combinator and this is what he wrote:[9]

Graham’s post has been widely controversial, with many researchers responding that they use these types of vocabularies. For many people for whom English is a second language or who normally use an extensive vocabulary, words like ‘delve’ are a part of their writing and not AI generated.

Another participant noted:

"Africans, mostly Nigerians, jumped on the Twitter (now X) thread to point out that we write that way. I actually do. It appears that AI is yet to learn the difference between English spoken or written as a first language and how those who got it as a second language communicate with it.

It is functional prejudice that has been taken on by AI. What do I mean? If you play word games online, especially those created by those who have English as their 1st language, you would be amazed at the words that pop up as correct options. This supposition is still being tested, though, but Africans use more of 'official' and 'bogus' words more than the owners of the language. AI may have picked up that trait from the owners of the language."

In general librarians agreed that neither Internet nor AI can replace the library and used Nile University in Egypt as an example:

"If the Internet could not replace libraries, I don't see how AI could take the place of a library. Remember, we provide many services, and for now, I have seen scholars use AI Mostly for research purposes. Any good researcher should know that in conducting research, you cannot depend on AI tools alone; you have to consult other information resources. Just like what Nile University library is undergoing, librarians should see the coming of AI to our advantage and introduce newer services such as information literacy, how to detect plagiarism, and ethical issues among others."

More broadly and beyond AI, libraries play an essential role for all members of the academic community:

"Libraries need to consider transforming their spaces in research and learning Commons. The trend is catching on fast as some libraries also have worker and creator spaces. The client should feel as though they are in a one-stop shop where they can learn something and transform it into a prototype or sample product. Not only can we help job seekers, but we can hold meetings with guest authors. We can, if funds permit, partner a publisher to bring an author’s work to life in the library. My personal concern is the lack of partnerships and the slow evolution in our library spaces and the lack of recognition for those who spark creativity. I miss the time many people would speak about a book or library inspiring them. The voices are few, and a new crop that rejects the education system (inclusive of the library) is getting popular. Save for the places with a strong reading culture and push for education."

The WhatsApp AI discussions were informative and spanned the breadth of existing and possible interactions with their constituencies. AfLIA has made recommendations for libraries that want to engage more fully with their university communities on this topic:

Lack of knowledge about technology creates unfounded trepidation. AfLIA encourages African librarians to view AI as a tool for discovering more knowledge and reference sources for their user communities. Generative AI is a Large Language Model that is trained using large mostly open datasets. Viewing it through this prism will give librarians the understanding that generative AI recycles and collates already existing knowledge. That is an area in which librarians excel! African librarians have another advantage—the datasets AI uses do not include sufficient African source material, AI source materials therefore underrepresent African knowledge. Academic librarians understand the importance of appropriately indexing content, which is essential when considering datasets. African academic libraries and other institutions, such as archives, contain source material coming from Africa—both original sources and research content about African knowledge.

Innovation in information access is unstoppable. It is imperative that academic librarians adopt an open and adaptive attitude toward new developments. AI, including generative AI, just as any other tool or resource, has its limitations. But being apprehensive and unreceptive towards AI, probably with the intention of gatekeeping ‘a profession under threat’, is not sustainable – a lesson history has taught us time and again. In fact, that mindset numbs the innovative capacity of librarians and institutions to adapt and provide valued services to fill the gaps developed because of the limitations of generative AI. We must embrace it as an opportunity to evolve and better serve our patrons.

The time has come for African academic librarians to deepen engagement and collaboration across universities, both locally and internationally. The challenges faced by the profession can no longer be considered local, hence operating in silos is not viable. Through collaboration, we can collectively debate, brainstorm, exchange best practices, and share insights on what actions or decisions are being taken by academic institutions to address pressing issues like academic ethics, plagiarism, originality of thought, copyright, misinformation, disinformation etc. that have resurfaced, following the birth of AI resources like ChatGPT and Gemini.

The application of information ethics principles is important while engaging with generative AI. African librarians can lead the way in teaching and inculcating ethical skills in the use of generative AI through information literacy skills or use of library tutorials. The Wikipedia article on ethics and AI outlines key points of intersection:[10]

"The ethics of artificial intelligence covers a broad range of topics within the field that are considered to have particular ethical stakes. This includes algorithmic biases, fairness, automated decision-making, accountability, privacy, and regulation ."

AfLIA strongly encourages African librarians to understand and promote Openness as an avenue for making datasets available for training generative AI. In an article on AI and data, published by European Data, the authors make a number of points about the relationship between AI and data, including:[11]

"Open data and AI have the potential to support and enhance each other’s capabilities. On the one hand, open data can improve AI systems. In general, exposing AI systems to a larger volume and variety of data increases the chance of the system returning accurate and useful predictions. As such, open data can be a supply of large amounts of diverse information for AI systems. In this way, the availability of open data contributes to better performing AI."

If African librarians are to play a role in discussions about data, openness, and AI, they must understand the importance of data. The AfLIA collaboration with Wikimedia on data short courses[12] is important. But this work must delve more deeply into the significance of these relationships.

Library and information institutions may not directly dictate the data utilized in training various generative AI models to ensure a balanced perspective on African knowledge. However, it is vital for stakeholders to intensify advocacy so that African researchers, educators, librarians, and authors in general can embrace openness. Making African knowledge more accessible through open research, open data, and open educational resources can improve the availability of diverse and representative data used to train AI models.

Related articles:

- Artificial Intelligence and the Underrepresentation of African Languages

- Three Ways Artificial Intelligence Could Change How We Use Open Educational Resources

- Opening Education: What Role Do Librarians on the African Continent Play?

[1] Neil Butcher, False Promises about ‘AI’ in Education. 19 April 2024. https://www.nba.co.za/encounters/blog/false-promises-about-ai-education

[2] See Wikipedia on store and forward messaging. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Store_and_forward - :~:text=Store and forward is a,or to another intermediate station.

[3] [3] Christine Kisiedu’s story featured in Rowing Upstream: Stories of the Information Age in Ghana published with Ford Foundation funding in 2002. It is available on the Wayback machine. Go to https://web.archive.org/web/20031220201222/http://www.piac.org/rowing_upstream/chapter7/ch7bringing.html for Christine’s recounting of email introduction into the University of Ghana.

[4] Go to AI, the Next Chapter for College Librarians by Lauren Coffee in Inside Higher Ed, November 3, 2023, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/tech-innovation/libraries/2023/11/03/ai-marks-next-chapter-college-librarians

[6] False promises about ‘AI’ in education, Neil Butcher, April 19, 2024, https://www.nba.co.za/encounters/blog/false-promises-about-ai-education

[7] Nkem Osuigwe, AfLIA-OER Africa Training WhatsApp group

[8] University of Ghana revises its plagiarism policy to clamp down on AI usage in academic work. Jemima Okang Addae. February 26, 2024. Graphic Online. https://www.graphic.com.gh/news/general-news/university-of-ghana-revises-its-plagiarism-policy.html - :~:text=The updated policy notably includes,unacceptable,’ the document stated

[9] Ana Altchek, Y Combinator cofounder Paul Graham says seeing this word in an email pitch is a sign it was written by ChatGPT, Business Insider. April 10, 2024. https://www.businessinsider.com/y-combinator-paul-graham-delve-ai-chatgpt-giveaway-email-pitch-2024-4

[10] Ethics of Artificial Intelligence, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ethics_of_artificial_intelligence - :~:text=The ethics of artificial intelligence covers a broad range of,accountability, privacy, and regulation.

[11] Open data and AI: A symbiotic relationship for progress. European Data. June 9, 2023. https://data.europa.eu/en/publications/datastories/open-data-and-ai-symbiotic-relationship-progress

[12] Wikidata short course, https://web.aflia.net/aflia-wikidata-online-course-registration-now-open/

Following the adoption of the OER Recommendation in 2019, UNESCO initiated a programme to support governments and educational institutions in implementing it.

One aspect of this programme was the development of a series of five guidelines to inform implementation of each Action Area in the Recommendation.

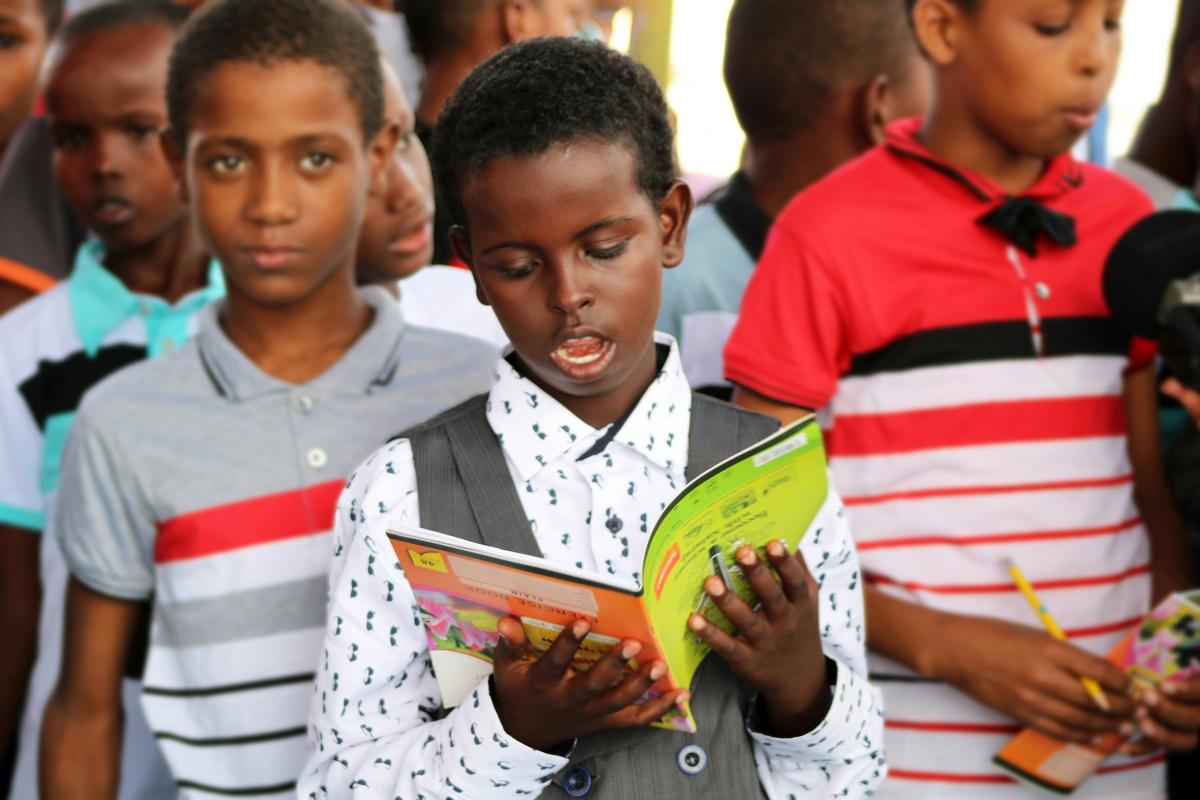

Image courtesy of Ismail Salad Osman Hajji dirir, Unsplash

As the digital age continues to reshape the global educational landscape in fundamental ways, the need for governments and educational institutions to champion Open Educational Resources (OER) has never been more relevant. Freely accessible, openly licensed educational content can help tackle some of the most pressing needs in education systems, including equity, access, and quality.

Following the adoption of the UNESCO Recommendation on OER at the 40th UNESCO General Conference in Paris on 25th November 2019, UNESCO initiated a programme to support governments and educational institutions in implementing the Recommendation.

One such action was the development of a series of five guidelines for governments. These guidelines were developed through a comprehensive consultative process and in cooperation with OER experts worldwide. They draw heavily on in-depth background papers prepared by OER experts from around the world in each of the five Action Areas of the OER Recommendation: Prof. Melinda dP. Bandalaria (building the capacity of stakeholders to create, access, re-use, adapt and redistribute OER); Dr Javiera Atenas (developing supportive policy); Dr Ahmed Tlili (encouraging inclusive and equitable quality OER); Dr Tel Amiel (nurturing the creation of sustainability models for OER), and Ms Lisbeth Levey (facilitating international cooperation).

OER Africa has provided logistical and editorial assistance to UNESCO on this work as part of a formal cooperation agreement with UNESCO to provide support in implementation of the OER Recommendation.

Aimed at governments and educational institutions, each set of guidelines has the following structure:

- An overview of recommendations in the Action Area;

- An introduction to the main issues surrounding the Action Area;

- A matrix of possible actions recommended for governments and institutions to implement each point in the Action Area;

- An in-depth discussion of the key issues surrounding the Action Area; and

- Examples of good practice.

By actively supporting and implementing the OER Recommendation, governments and educational institutions can not only make high quality education more accessible but can also promote transformation in their education systems. This commitment to OER is essential for building resilient, adaptable education systems that can meet the demands of a rapidly changing world.

Related articles

With the ever-increasing costs of textbooks, how can university students get access to the resources they need to study? This article examines the benefits of using open textbooks in the Global South.

Image: CC0 (Public domain)

With the ever-increasing costs of textbooks, how can university students get access to the resources they need to study?

Worldwide, university students find it difficult to purchase textbooks for their courses as they are too expensive. Already in 2014 in South Africa[1], and in 2011 in the United States[2], there were reports that students didn’t buy textbooks due to expense. The situation has not improved in recent years; for example, in a study of nearly fifty thousand respondents in South African universities, nearly two thirds indicated that they spent between R500 and R2500 on textbooks, and while 87% of students’ first semester modules had prescribed textbooks, 27% of students did not buy any prescribed books in the first semester of 2020. Students were opting not to purchase textbooks either because of a lack of affordability, because they did not find them contextually relevant, or because a course would only use a small portion of the textbook. [3]

Open textbooks can be regarded as a subset of Open Educational Resources (OER). They are digital textbooks published under an open licence, which means that they are freely downloadable and adaptable to suit a range of contexts (as long as the licence permits adaptation). The right to adapt is particularly important for educators who may want to tailor the textbook to their specific curriculum. An open textbook can be published with different Creative Commons licences,[4] depending on how open or restrictive the author wishes the licence to be. The principal advantages of an open textbook are its accessibility and affordability to the students, as long as they have a digital device, or have access to print at low or no cost. However, open textbooks have other advantages as well. These include:[5]

- Local Contexts: Open textbooks can be regularly updated, and tailored to suit the local context, providing cultural relevance and addressing specific needs of students.

- Partial Use: In some courses, only a portion of the overall textbook content is relevant. Students may hesitate to purchase an expensive textbook when they will only use a few chapters. In contrast, open textbooks allow educators to select and integrate specific sections, reducing unnecessary costs.

- Collective Authorship: Open textbooks encourage collaborative authorship strategies. Locally produced open textbooks can involve input from multiple experts, resulting in richer and more contextually relevant content with diverse perspectives.

- Flexibility: Open textbooks can be accessed in different formats and stored digitally, so that they are easy to share and adapt.

Of course, open textbooks also have some disadvantages, namely:

- Availability: We provide examples of open textbook repositories below, but educators may find that there is limited selection for certain subjects or specialised topics.

- Quality: There may be inconsistencies in writing style, accuracy, and depth of content but these can be easily mitigated by evaluating the textbooks prior to use, as should be done for all resources to be used, including commercial textbooks.

- Author incentives: Authors of traditional textbooks normally receive royalties from publishers as their books are sold. The open licence by which open textbooks are released means that other forms of incentive may be needed, for example in the form of grants, that may not be sufficiently enticing for many potential authors.

Research on open textbooks

Most research has been carried out in the Global North. For example, a meta-analysis of 22 studies of 100,012 students found that there were no differences between open and commercial textbooks for learning performance.[6] A research study Adoption and impact of OER in the Global South[7] had similar findings, with open textbooks being more effective that traditional ones in several instances. However, the studies reported that careful pedagogical scaffolding, including a mix of OER, produced the most effective learning. Within Africa, research findings from the Digital Open Textbooks for Development (DOT4D) Project[8] found that open textbooks addressed economic, cultural, and political injustices faced by their students, issues not considered by traditional textbooks. Summarising the research overall, we can say that open textbooks have several advantages over traditional ones, as listed above, and in terms of learning, they are equivalent.

Examples of African institutions who have benefited from using open textbooks

Probably the best example of collaborative development of open textbooks is the University of Cape Town’s DOT4D Project. If you want to learn about the experiences of their staff and students, read UCT Open Textbook Journeyswhich documents the stories of 11 academics at the University who embarked on open textbook development initiatives to provide their students more accessible and locally relevant learning materials.

Other African universities’ libraries list sites where open textbooks and other OER are available, usually from outside the continent. Finding open textbooks for your own institution is not always easy. Here we list three sites where you can search for open textbooks. Bear in mind that, if you choose an American or European textbook, you may need to spend time adapting it for your own context.

University of Cape Town Catalogue

26 textbook titles ranging from medical texts, through sustainable development to marketing, but also many other titles on OpenUCT.

Based at the University of Minnesota in the United States, this repository has 1,403 titles. The view shown here groups the titles by subject.

This LibGuide lists 17 platforms where you can search for open access textbooks and other free books.

Resources on developing and using open textbooks

Below is a list of resources to help you explore this growing field. The first three assist you to develop an open textbook, while the last two guide you to adopt or modify an existing open textbook.

- Commonwealth of Learning Guide to Developing Open Textbooks

- Open Education Network: Authoring Open Textbooks

- Rebus Community: A guide to making open textbooks with students

- BC Campus: Steps to Adopting an Open Textbook

- Open Education Network: Modifying an Open Textbook: What You Need to Know

Finally, although they are not designed for higher education, the open textbooks developed by Siyavula for high school mathematics, technology, and sciences may be useful for colleges and access courses in universities.

In summary, there are considerable benefits to using open textbooks, but with a few exceptions, African institutions have not yet taken on the challenge of producing open textbooks themselves. Clearly, funding is required for the development of open textbooks, and institutions might consider making funding applications to create (or adapt) these highly useful open education resources for the benefit of more African students.

Related resources:

- Researching OER initiatives in African higher education

- The Revised Open Knowledge Primer for African Universities

- Self-Publishing Guide: BC Open Textbook

Access the OER Africa communications archive here

[1] Nkosi, B. (2014). Students hurt by pricey textbooks. Mail & Guardian. Retrieved from https://mg.co.za/article/2014-10-03-students-hurt-by-pricey-textbooks/

[2] Redden, M. (2011). 7 in 10 Students Have Skipped Buying a Textbook Because of Its Cost, Survey Finds. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from https://www.chronicle.com/article/7-in-10-students-have-skipped-buying-a-textbook-because-of-its-cost-survey-finds/

[3] Department of Higher Education. (2020). Students’ Access to and use of Learning Materials—Survey Report 2020. Retrieved from https://www.usaf.ac.za/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/DHET_SAULM-Report-2020.pdf

[4] See https://creativecommons.org/share-your-work/cclicenses/#:~:text=Creative%20Commons%20licenses%20give%20everyone,creative%20work%20under%20copyright%20law.

[5] Digital Open Textbooks for Development. (2021). ‘Open Textbooks in South African Higher Education’ Roundtable Report. University of Cape Town. Retrieved from https://open.uct.ac.za/server/api/core/bitstreams/3a7e1a09-0617-4ba4-b6dd-4572bd870d60/content

[6] Clinton, V. and Khan, S. (July 2019). ‘Efficacy of Open Textbook Adoption on Learning Performance and Course Withdrawal Rates: A Meta-Analysis’ AERA Open. 5 (3): 233285841987221. doi:10.1177/2332858419872212. ISSN 2332-8584.

[7] Hodgkinson-Williams, C. & Arinto, P. B. (2017). ‘Adoption and impact of OER in the Global South’. Cape Town & Ottawa: African Minds, International Development Research Centre & Research on Open Educational Resources. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.1005330